When you hear the name Graves' disease is an autoimmune disorder that triggers the thyroid gland to produce excessive thyroid hormones, you probably think of rapid heartbeat, weight loss, and bulging eyes. What many don’t realize is that the hormone surge can also strain the kidneys, sometimes quietly undermining their ability to filter blood. This guide walks you through how the thyroid‑kidney connection works, what signs to watch for, and practical steps to protect renal health while managing Graves'.

Understanding Graves' Disease

Graves' disease belongs to the broader family of hyperthyroidism disorders. The immune system mistakenly creates thyrotropin‑receptor antibodies (TRAb) that bind to the thyroid‑stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor, forcing the gland to secrete too much thyroid hormone-mainly triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). The resulting metabolic acceleration can raise resting heart rate, increase blood pressure, and boost the body’s overall oxygen demand.

Because the kidneys are central to regulating blood volume, electrolytes, and waste removal, any systemic upheaval-like the one caused by excess T3/T4-has a ripple effect on renal function.

How Thyroid Hormones Influence the Kidneys

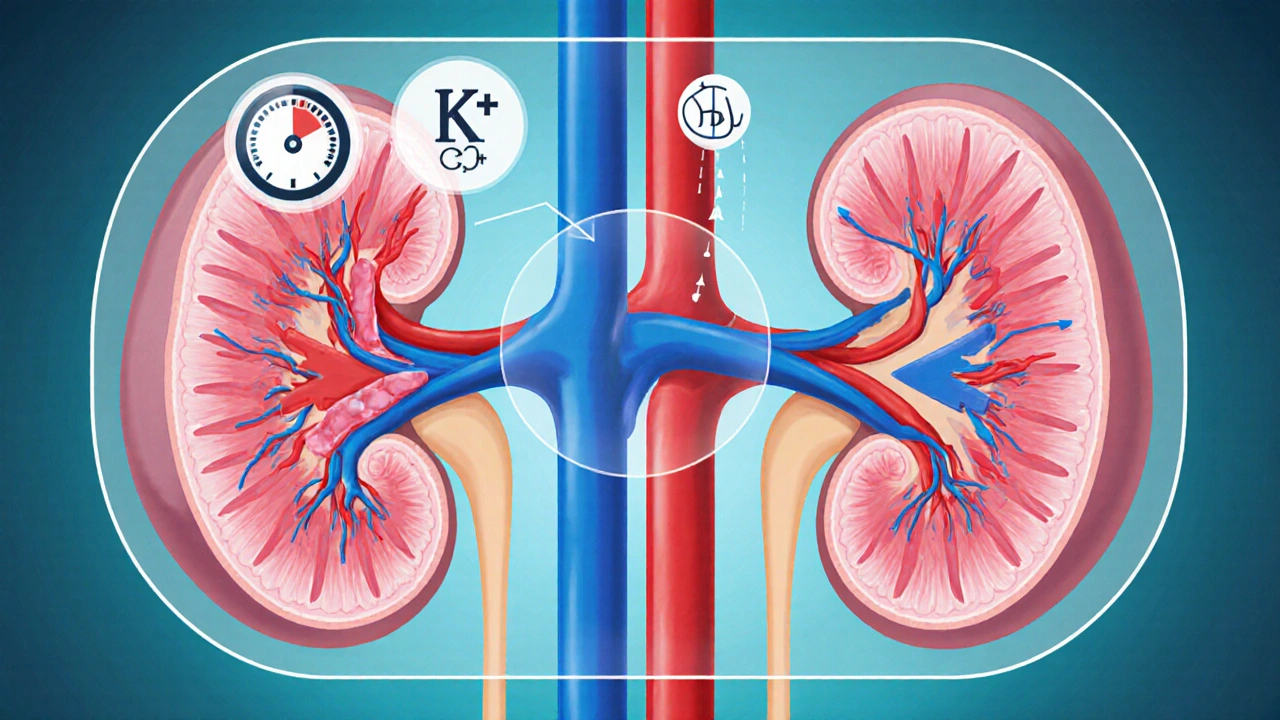

Thyroid hormones affect the kidneys in three principal ways:

- Renal blood flow. Elevated T3/T4 dilates the renal arteries, temporarily increasing glomerular filtration rate (GFR). While a higher GFR might look good on paper, the surge can stress the delicate glomerular capillaries.

- Renin‑Angiotensin System (RAS). Hyperthyroidism stimulates renin release, which raises angiotensin II levels and leads to vasoconstriction and hypertension-both risk factors for chronic kidney disease (CKD).

- Electrolyte handling. Excess thyroid hormone speeds up tubular reabsorption, potentially causing low potassium (hypokalemia) and calcium imbalances that impair renal concentrating ability.

These mechanisms explain why patients with uncontrolled Graves' often present with subtle kidney‑related lab changes before any overt symptoms appear.

Common Renal Complications Linked to Graves' Disease

| Effect | Mechanism | Typical Clinical Sign |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated GFR (hyperfiltration) | Increased cardiac output & renal artery dilation | Low serum creatinine, high 24‑hour urine protein |

| Hypertension | Renin‑angiotensin activation | Consistently high blood pressure readings |

| Electrolyte imbalance | Accelerated tubular reabsorption | Hypokalemia, hypercalciuria |

| Proteinuria (often mild) | Glomerular stress from hyperfiltration | Albumin/creatinine ratio >30mg/g |

| Progressive CKD (rare) | Chronic hypertension + persistent hyperfiltration | Declining eGFR over years |

Most of these changes are reversible when thyroid levels are brought back into the normal range, but long‑standing hyperthyroidism can set the stage for permanent damage.

Diagnosing Kidney Involvement in Graves' Patients

Because early renal signs are often silent, doctors rely on a combination of blood tests, urine analysis, and imaging:

- Serum creatinine & eGFR. A sudden dip in creatinine may actually signal hyperfiltration rather than improvement.

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Elevated BUN alongside high GFR can hint at dehydration-a common issue when thyroid metabolism is high.

- Urine albumin‑to‑creatinine ratio (UACR). Even mild albuminuria warrants closer monitoring.

- Renal ultrasound. Helpful for ruling out structural anomalies if CKD is suspected.

- Thyroid function tests (TSH, Free T4, Free T3). Always interpreted together with renal labs to see cause‑effect patterns.

Guidelines suggest checking renal panels at baseline, then every 3-6months while thyroid hormones are unstable, and annually once euthyroid status is maintained.

Managing Kidney Health While Treating Graves' Disease

Effective management hinges on two parallel tracks: controlling the thyroid and safeguarding the kidneys.

1. Choose the Right Thyroid Therapy

Options include antithyroid drugs (ATDs), radioactive iodine (RAI), and surgery. Each carries its own renal considerations:

- Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil). Generally safe for kidneys, but rare cases of acute interstitial nephritis have been reported. Monitoring liver enzymes is more common, yet a baseline renal panel is prudent.

- Radioactive iodine. Can trigger a transient surge in thyroid hormone release (the “thyroid storm” effect) that spikes blood pressure and GFR. Pre‑treatment beta‑blockers help blunt this response.

- Surgical thyroidectomy. Offers rapid hormone control, but peri‑operative fluid shifts can affect kidney perfusion. Adequate hydration and careful anesthesia are essential.

2. Control Blood Pressure

Since hypertension is a key driver of CKD, aim for a target < 130/80mmHg. ACE inhibitors or ARBs not only lower pressure but also reduce proteinuria, providing a double‑benefit for Graves' patients.

3. Stay Hydrated

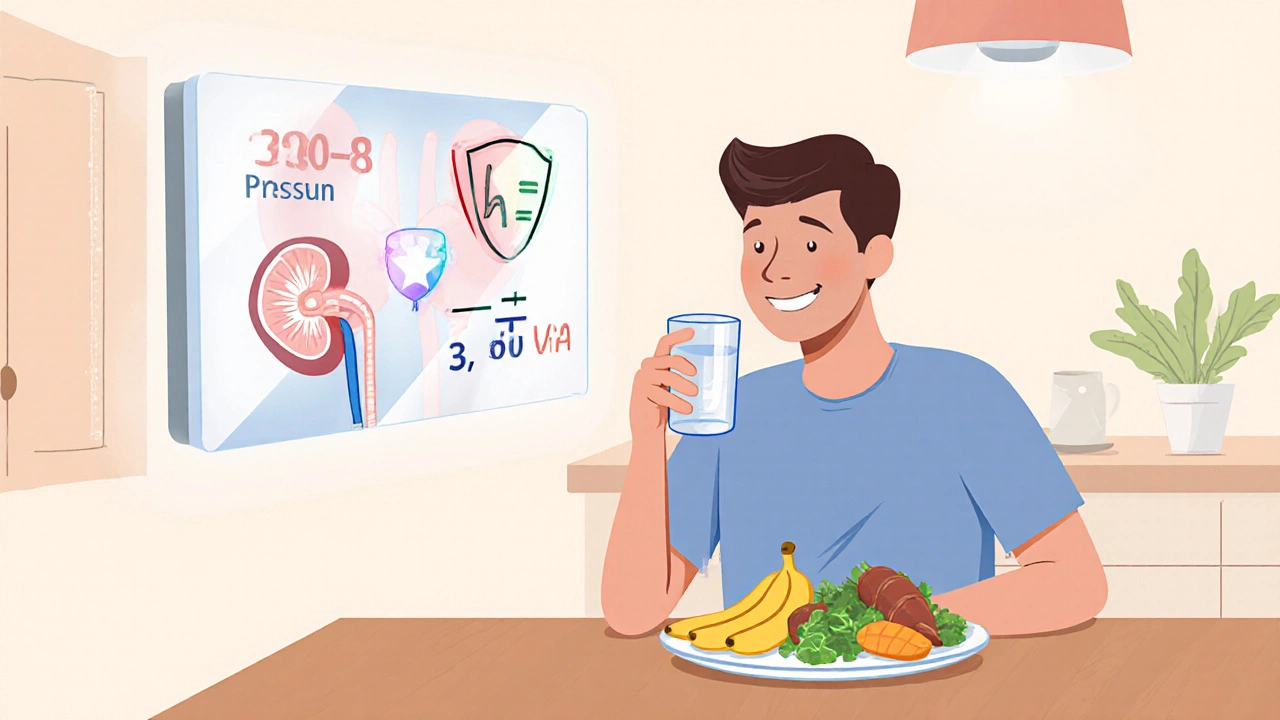

Hypermetabolism increases insensible water loss. Encouraging at least 2.5L of fluid daily (adjusted for activity level) helps maintain renal perfusion and prevents BUN spikes.

4. Mind the Electrolytes

Regularly check serum potassium and calcium. If hypokalemia appears, supplement with potassium‑rich foods (bananas, sweet potatoes) before reaching for prescription doses.

5. Nutrition for Dual Benefits

A diet low in sodium (≤1,500mg/day) eases blood pressure, while adequate protein (0.8g/kg body weight) supports muscle mass without overloading the kidneys. Emphasize leafy greens, berries, and fatty fish for their anti‑inflammatory omega‑3s, which may dampen autoimmune activity.

6. Regular Monitoring Schedule

Set up a joint follow‑up between your endocrinologist and nephrologist. A practical checklist looks like this:

- Every 3months: TSH, Free T4, Free T3, blood pressure, serum creatinine, eGFR.

- Every 6months: UACR, electrolytes, lipid profile.

- Annually: Renal ultrasound (if prior abnormalities), bone density (hyperthyroidism can affect calcium metabolism).

When to Seek Specialist Care

If any of the following occur, it’s time to involve a nephrologist:

- eGFR drops below 60mL/min/1.73m² and stays low for more than three months.

- Persistent proteinuria (>300mg/day) despite thyroid control.

- Unexplained rises in blood pressure after thyroid treatment begins.

- Symptoms of fluid overload: swelling in ankles, shortness of breath, or rapid weight gain.

Early referral can prevent irreversible kidney damage and tailor medication doses to your current renal status.

Living Well with Graves' Disease and Healthy Kidneys

Beyond medical management, lifestyle tweaks make a big difference:

- Stress reduction. Chronic stress raises cortisol, which can compound thyroid and renal strain. Try mindfulness meditation or gentle yoga.

- Regular exercise. Aim for moderate cardio (30minutes most days). It improves heart health, lowers blood pressure, and helps maintain muscle mass, which in turn supports kidney function.

- Avoid nephrotoxic agents. Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), certain antibiotics, and excessive contrast dye can hurt kidneys, especially when the thyroid is still fluctuating.

- Quit smoking. Smoking worsens autoimmune activity and accelerates vascular damage, both bad news for kidney health.

By blending medical treatment with these everyday habits, you can keep both your thyroid and kidneys running smoothly.

Key Takeaways

- Graves' disease can raise GFR, cause hypertension, and lead to mild proteinuria through excess thyroid hormones.

- Regular kidney labs, blood pressure checks, and electrolyte monitoring are essential while treating hyperthyroidism.

- Choosing the right thyroid therapy, staying hydrated, and using ACE inhibitors or ARBs when needed protect renal function.

- Early nephrologist involvement is crucial if eGFR declines, proteinuria persists, or blood pressure spikes.

- Lifestyle choices-low‑salt diet, adequate fluid, stress management-support both thyroid and kidney health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Graves' disease cause kidney failure?

Kidney failure is rare, but prolonged uncontrolled hyperthyroidism can lead to chronic hypertension and persistent hyperfiltration, which may eventually damage the kidneys enough to cause stage3 or higher chronic kidney disease. Early thyroid control dramatically lowers this risk.

How often should kidney function be tested in Graves' patients?

At diagnosis, get a baseline serum creatinine, eGFR, and urine albumin‑to‑creatinine ratio. Repeat these labs every 3‑6months while thyroid hormones are unstable, then yearly once euthyroid status is maintained.

Do antithyroid drugs affect the kidneys?

Methimazole and propylthiouracil are mainly linked to liver concerns, but rare cases of drug‑induced interstitial nephritis have been reported. Routine renal monitoring is advisable, especially if you notice swelling or changes in urine output.

Is dialysis ever needed for Graves' disease?

Dialysis is only required if kidney disease progresses to end‑stage renal failure, which is uncommon in Graves' patients who receive timely thyroid treatment. The focus remains on preventing that scenario through blood pressure control and hormone stabilization.

Can lifestyle changes reverse kidney issues caused by Graves'?

If the kidney changes are due to hyperfiltration or mild hypertension, achieving euthyroid status and adopting a low‑salt, well‑hydrated diet can often normalize GFR and reduce proteinuria. More severe damage may improve but rarely returns completely to pre‑disease levels.

Russell Martin October 16, 2025

Hey folks, keep an eye on your blood pressure and stay hydrated-your kidneys will thank you! Remember to get those thyroid labs checked every few months, it's the easiest way to spot issues early. Don't forget to watch teh electrolytes. Stay motivated and you'll feel better in no time.

Jenn Zee October 18, 2025

It is a profound societal failure when individuals with a condition as intricate as Graves' disease ignore the cascading impact on renal physiology. The literature, replete with rigorous studies, unequivocally demonstrates that unchecked hyperthyroidism precipitates hyperfiltration, hypertension, and eventual proteinuria. Yet, in the noisy chorus of superficial health advice, this nuance is routinely obscured. One must approach the management of such endocrine‑renal interplay with scholarly diligence, not with the cavalier optimism of a quick‑fix mentality. The ethical responsibility of the clinician extends beyond merely normalising TSH; it encompasses vigilant monitoring of eGFR, albumin‑creatinine ratios, and electrolyte panels. Moreover, patients are obliged to adopt lifestyle modifications that reflect an awareness of their intertwined organ systems. It is disconcerting to observe a growing trend of patients dismissing the importance of regular blood pressure checks, as if hypertension were an optional accessory. The socioeconomic determinants of health further complicate the picture, demanding that providers advocate for equitable access to nephrology follow‑up. Failure to appreciate these layers is tantamount to intellectual negligence. In this context, the recommendation to hydrate adequately is not a trivial suggestion but a cornerstone of renal preservation. Similarly, the admonition to limit sodium intake should be couched in evidence‑based guidelines rather than vague admonitions. The integration of ACE inhibitors or ARBs, when indicated, exemplifies a proactive stance that aligns with best practice standards. It is incumbent upon us, as both scholars and caregivers, to disseminate this knowledge without the patronising tone that pervades much of popular health discourse. To disregard the renal ramifications of Graves' disease is to perpetuate a myopic view of medicine. Therefore, let us champion a holistic approach, anchored in rigorous monitoring, patient education, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Only then can we hope to mitigate the silent erosion of kidney function that this endocrine disorder can engender.

don hammond October 19, 2025

Oh sure, because everyone has time to read a 15‑sentence dissertation while juggling their meds 😂. If only the thyroid itself could send us a reminder email, right? 🙃

Ben Rudolph October 20, 2025

Your analysis completely overlooks the social determinants that truly drive health outcomes.

Ian Banson October 22, 2025

Look, the science doesn't care about your sociopolitical narratives – the physiology of hyperthyroidism and renal stress is the same whether you're in London or Philadelphia, and the data speak for themselves.

marcel lux October 23, 2025

Thanks for the thorough breakdown, everyone. I think the key takeaway is to sync endocrinology and nephrology appointments so we don’t miss any subtle changes. Let’s keep sharing practical tips and stay supportive of each other’s journeys.

Charlotte Shurley October 24, 2025

I appreciate the collaborative spirit. Regular joint follow‑ups are indeed essential for early detection and intervention.

Judson Voss October 26, 2025

Many of the suggestions here sound like common sense, yet patients often neglect them, which is frankly disappointing and indicates a lack of personal responsibility.

Elizabeth Post October 27, 2025

Let’s focus on encouraging positive habits rather than blaming. Small, consistent steps can lead to lasting improvements in both thyroid and kidney health.

Brandon Phipps October 29, 2025

One thing I’ve noticed in practice is that the timing of lab draws can really influence how we interpret kidney function in hyperthyroid patients. For instance, if you obtain a serum creatinine right after a thyroid storm, the GFR may appear artificially high due to transient hyperfiltration. It helps to schedule the renal panel during a stable euthyroid phase, preferably a week after any dose adjustments. Additionally, pairing the eGFR with a urine albumin‑to‑creatinine ratio gives a clearer picture of underlying glomerular stress. Hydration status is another hidden variable – encourage patients to log their fluid intake and watch for signs of dehydration, especially in warm climates. When prescribing ACE inhibitors, start low and monitor potassium, since hyperthyroidism can already predispose to hypokalemia. Educating patients about the synergistic effect of diet, medication, and stress management can empower them to take charge of both systems. Finally, don’t underestimate the value of a multidisciplinary conference where endocrinologists and nephrologists review the same case together – it often uncovers nuances that one specialty might miss.

Akinde Tope Henry October 30, 2025

Schedule labs during stable phases; monitor both TSH and eGFR.