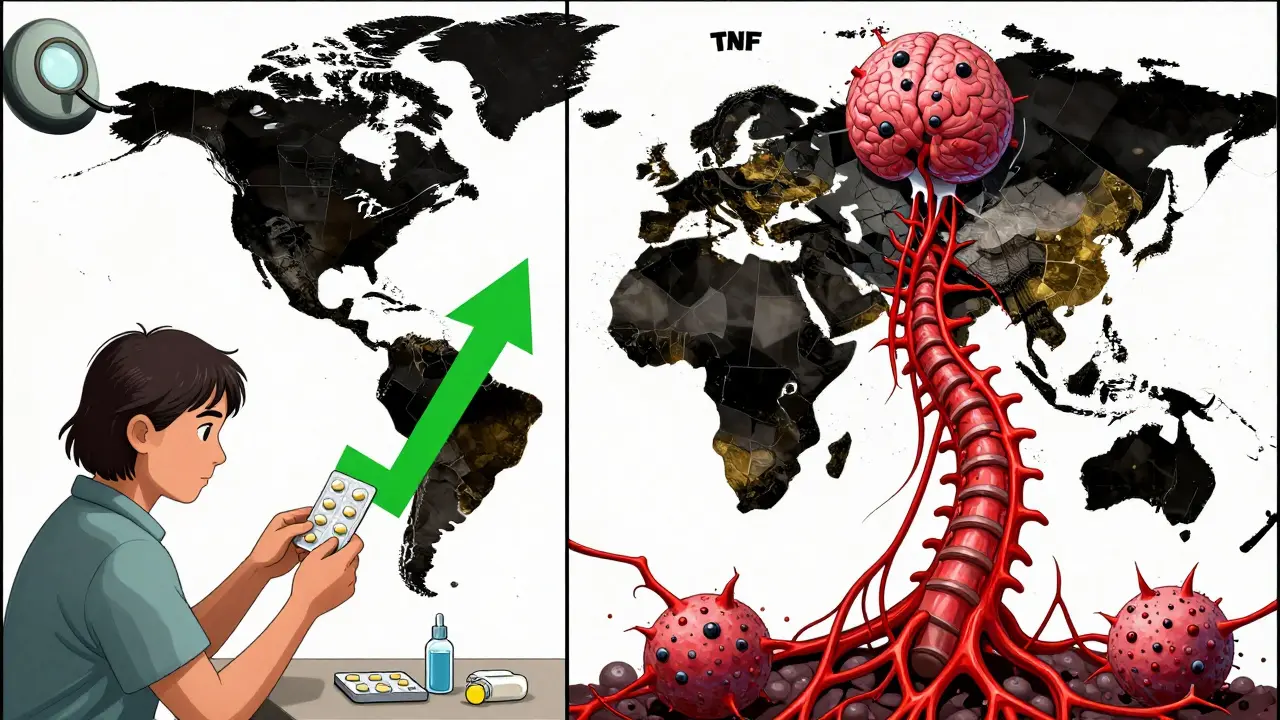

TNF Inhibitor TB Risk Comparison Tool

Relative TB Reactivation Risk

3.2x times higher risk compared to etanercept

High Risk for infliximab and adalimumab

Low Risk for etanercept

Why This Difference Matters

Infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies that block both free-floating and membrane-bound TNF. This disrupts granulomas (the body's containment structures for TB), allowing dormant TB to reactivate. Etanercept works differently by acting as a decoy receptor, leaving membrane-bound TNF mostly intact, which helps maintain granuloma integrity and significantly reduces TB reactivation risk.

Personalized Recommendations

Key Considerations

- TB Screening is essential: Both TST and IGRA should be performed before starting TNF inhibitors.

- High-risk patients: Consider etanercept if you're from a high TB burden country (India, Philippines, Nigeria).

- Even with negative tests: 18% of TB cases occur in patients with negative pre-treatment tests. Continue symptom monitoring.

- Treatment duration: The new 4-month rifampin/isoniazid regimen shows 89% adherence compared to 68% with traditional 9-month isoniazid.

When doctors prescribe TNF inhibitors for conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or Crohn’s disease, they’re targeting a powerful driver of inflammation. These drugs - including infliximab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks tumor necrosis factor-alpha, adalimumab, another monoclonal antibody with similar action, and etanercept, a soluble TNF receptor - work by shutting down a key immune signal called TNF-alpha. But in doing so, they also weaken the body’s ability to contain hidden infections, especially latent tuberculosis (LTBI), a dormant form of TB that affects up to one-quarter of the global population. The result? A real and measurable spike in active TB cases among people taking these medications.

Why Some TNF Inhibitors Are Riskier Than Others

Not all TNF inhibitors carry the same risk. Data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register shows that patients on infliximab or adalimumab are more than three times as likely to develop TB as those on etanercept. Why? It comes down to how each drug interacts with the immune system at a cellular level. Infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies that bind tightly to both free-floating and membrane-bound TNF. This blocks the signal completely - but membrane-bound TNF is essential for keeping TB bacteria locked inside granulomas, the body’s natural containment structures. When that signal is wiped out, granulomas fall apart, and TB wakes up. Etanercept works differently. It’s a fusion protein that acts like a decoy receptor. It soaks up excess TNF but leaves membrane-bound TNF mostly untouched. That’s why its TB risk is far lower - studies show it’s only about one-fifth as risky as the antibody-based drugs.Screening Isn’t Optional - It’s Life-Saving

Before anyone starts a TNF inhibitor, screening for latent TB is non-negotiable. The American Thoracic Society, CDC, and Infectious Diseases Society of America all agree: you must test. Two tools are used: the tuberculin skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). Each has strengths and limits. TST is cheaper and widely available, but can give false positives if you’ve had the BCG vaccine. IGRA is more specific, especially in vaccinated people, but costs more and isn’t available everywhere. A 2019-2024 study of 519 patients found that 87% received TST, 37% got a booster TST, and only 6% got IGRA. That’s not enough. Guidelines now recommend IGRA for high-risk patients - especially those from countries with high TB rates. In places like India, the Philippines, or Nigeria, where TB is common, even a negative test doesn’t guarantee safety. That’s why the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) says: if you’re from a high-burden country, treat for latent TB even if your test is negative.Treatment Before Therapy

If you test positive for latent TB, you don’t start the TNF inhibitor right away. You treat the TB first. The gold standard used to be nine months of isoniazid. But adherence was terrible - nearly a third of patients quit because of liver concerns or just forgetting pills. That’s changing. In 2024, the FDA approved a new 4-month regimen combining rifampin and isoniazid. Clinical trials showed adherence jumped from 68% to 89%. That’s huge. It means more people complete treatment, and fewer develop active TB later. Isoniazid, a first-line TB drug can cause liver damage, especially in older adults or those with alcohol use. That’s why liver enzymes are checked before and during treatment. But skipping treatment because of fear is riskier than the side effects. A single case of active TB on a TNF inhibitor can be deadly.What Happens Even After Screening?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: screening isn’t perfect. A review of 1,200 patients across five clinics found that 18% of those who developed TB had negative screening results. Why? Some people get infected right before starting the drug - their bodies haven’t had time to react yet. Others have false negatives because their immune systems are already suppressed by other medications. And some infections are so early, the test just can’t detect them. That’s why monitoring doesn’t stop after the first dose. Patients need to be watched closely for the first year. Every three months, doctors should ask: Have you had fever? Night sweats? Unexplained weight loss? A cough that won’t go away? These aren’t just symptoms - they’re red flags. In patients on TNF inhibitors, TB often spreads beyond the lungs. Up to 78% of cases involve the spine, lymph nodes, or even the brain - making diagnosis harder and treatment more urgent.When TB Strikes: TB-IRIS and Other Complications

Sometimes, when you start treating TB in someone who’s been on a TNF inhibitor, their immune system overreacts. This is called TB-IRIS - immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. It happens when the immune system wakes up, fights the TB bacteria too hard, and causes swelling, pain, and fever. It’s not the infection getting worse - it’s the body’s own response. In one study, 12.7% of patients on anti-TNF therapy developed TB-IRIS after starting TB treatment. Most cases appeared about 110 days after their last TNF inhibitor dose. Treatment often requires high-dose steroids for months. It’s complicated, scary, and avoidable - if screening and timing are done right.

Global Disparities and Real-World Challenges

In the U.S., where TB is rare, the absolute risk is low - but it’s still there. In high-burden countries, the risk jumps dramatically. WHO reports that 80% of rheumatology clinics in low-resource settings can’t even access IGRA testing. Many patients never get screened at all. And when they do, follow-up care is patchy. One rheumatology nurse on Reddit shared a case: a patient from Bangladesh tested negative, started adalimumab, and developed miliary TB - a deadly, widespread form - within four months. Cost is another barrier. Screening adds $150-$300 to initial treatment. But compared to the cost of treating active TB - which can run over $100,000 in hospital stays, antibiotics, and long-term care - screening is a bargain. And it saves lives.The Future: Safer Drugs Are Coming

Researchers are already working on next-generation TNF inhibitors that don’t disrupt granulomas. Early animal studies show a new class of drugs - like those targeting CD271 - reduce TB reactivation risk by 80% compared to current drugs. These are still in Phase II trials, but they offer real hope. The goal isn’t just to treat inflammation - it’s to do it without leaving patients vulnerable to deadly infections.What You Need to Do

If you’re considering a TNF inhibitor:- Ask for a TB test - TST or IGRA - before your first dose.

- If you’re from a country with high TB rates, insist on treatment even if your test is negative.

- If you’re positive for latent TB, complete the full 4-month or 9-month regimen before starting the biologic.

- Report any fever, night sweats, weight loss, or cough immediately - even months after starting treatment.

- Don’t skip follow-ups. TB can strike even after a year.

If you’re a provider:

- Use IGRA for high-risk patients.

- Consider the 4-month rifampin/isoniazid regimen - it works better and sticks better.

- Don’t rely on one negative test. Repeat if symptoms appear.

- Remember: extrapulmonary TB is common in these patients. Think beyond the lungs.

Can I get TB even if my screening test was negative?

Yes. Screening tests aren’t perfect. About 18% of TB cases in TNF inhibitor users happened in people with negative pre-treatment tests. This can occur if you were recently exposed, have a weak immune response, or the infection was too early to detect. That’s why ongoing symptom monitoring is just as important as the initial test.

Which TNF inhibitor has the lowest risk of TB reactivation?

Etanercept has the lowest risk. Studies show its TB reactivation rate is about one-fifth that of infliximab or adalimumab. This is because etanercept spares membrane-bound TNF, which helps maintain granulomas that contain TB bacteria. It’s still a risk - but significantly lower.

Do I need to be screened if I’ve had the BCG vaccine?

Yes. The BCG vaccine can cause false positives on the tuberculin skin test (TST), making it hard to interpret. That’s why interferon-gamma release assays (IGRA) are preferred for vaccinated individuals. IGRA doesn’t react to BCG and gives clearer results. If you’ve had BCG, ask your doctor about using IGRA instead of or alongside TST.

How long after starting a TNF inhibitor does TB usually appear?

Most cases occur within the first 3 to 6 months of starting treatment. However, TB can develop at any time - even after a year. The highest risk is in the first year, which is why quarterly symptom checks are recommended during that time.

Is TB more dangerous for people on TNF inhibitors?

Yes. TB in patients on TNF inhibitors is often more severe. It’s more likely to be extrapulmonary - affecting the spine, brain, or lymph nodes - and harder to diagnose. Mortality rates are 23% higher than in community-acquired TB. Early detection and treatment are critical.

Managing TB risk with TNF inhibitors isn’t about fear - it’s about smart, consistent care. Test before you start. Treat if needed. Watch for symptoms. The science is clear. The protocols exist. The tools are available. What matters now is making sure they’re used - every time, for every patient.

Shelby Price February 4, 2026

I had no idea etanercept was so much safer than the other biologics. My rheumatologist just threw infliximab at me like it was the only option. Time to do some research and ask for a switch.

Thanks for laying this out so clearly.

Jesse Naidoo February 5, 2026

This is why I don't trust Big Pharma. They push the most profitable drugs, not the safest ones. Etanercept costs less? Then why are they marketing the others like they're magic bullets? Something's fishy.

Sherman Lee February 6, 2026

TB reactivation? 😳 I've been on adalimumab for 2 years. My doc never even mentioned this. Are you telling me I'm basically a walking TB time bomb? I'm gonna need a second opinion. Like, stat.

Lorena Druetta February 7, 2026

To every patient reading this: Your health is worth fighting for. Please, please, please ask your doctor about IGRA testing. If they hesitate, ask why. You deserve to be informed. This is not fear-mongering-it is empowerment.

Zachary French February 8, 2026

So let me get this straight-these drugs are basically unchaining TB like it's a horror movie monster? And we’re just supposed to trust that one test will catch it? Lol. I’ve seen more reliable weather forecasts. This whole system is a dumpster fire.

Coy Huffman February 8, 2026

I’ve been thinking a lot about how medicine balances risk these days. We treat inflammation aggressively, but we forget the body’s natural defenses aren’t just backup systems-they’re the foundation. Etanercept’s mechanism feels more like working with the body than overriding it.

Caleb Sutton February 9, 2026

They’re lying. The CDC knows TB is being used as an excuse to push expensive drugs. They want you scared so you’ll take the $10K/month biologics. I’m not falling for it.

Jamillah Rodriguez February 10, 2026

I started etanercept last year. Got the IGRA, tested negative, skipped the treatment. Still feel great. But now I’m paranoid every time I sneeze. 😅

Katherine Urbahn February 11, 2026

It is imperative, non-negotiable, and ethically mandatory that clinicians adhere to the ATS/CDC/IDSA guidelines. Failure to do so constitutes negligence. The data is unequivocal. Do not rely on TST alone in BCG-vaccinated individuals. The consequences are dire.

Joy Johnston February 13, 2026

I’m a nurse in a rheumatology clinic. We switched to the 4-month combo last year. Compliance went from ‘meh’ to ‘wow.’ Patients actually finish it. And yes-we’ve had zero TB cases since. It works. Just follow the protocol.

Amit Jain February 14, 2026

In India, most patients can't even afford TST. We use it only if they can pay. Many start biologics without testing. TB comes later. Then they blame the drug. But it’s not the drug-it’s the system.

Kunal Kaushik February 14, 2026

I’m from Delhi. Got BCG as a kid. My doc in the US said IGRA is better. Did it-negative. But I still took the 4-month course. Better safe than sorry. My mom says I’m overcautious. I say: I’m alive.

Mandy Vodak-Marotta February 15, 2026

Okay, so I’ve been on adalimumab for 3 years. I had the TST, it was positive, I did the 9 months of isoniazid, I was miserable, my liver was all over the place, and now I’m wondering if I even needed it? Like, what if I was just a false positive? And now I’m stuck with this drug and I’m scared to stop because my joints will turn to dust. I just need someone to tell me I’m not crazy for feeling this way.

Alec Stewart Stewart February 16, 2026

To anyone reading this who’s scared: You’re not alone. I was terrified when I got my positive IGRA. But I did the 4-month combo, and honestly? It was way easier than I thought. My doc held my hand through it. You can do this. And you’re not weak for needing help. You’re smart.

Samuel Bradway February 16, 2026

My cousin got miliary TB after starting infliximab. She was 28. She’s fine now, but it took 6 months in the hospital. Don’t skip the screening. Seriously.