Adolescent Medication Monitoring Calculator

Medication Monitoring Guide

This tool helps determine appropriate monitoring frequency based on FDA guidelines for adolescent psychiatric medication use. Critical monitoring is required especially during the first 4 weeks of treatment.

When a teenager starts taking psychiatric medication, the goal is relief - less anxiety, better sleep, fewer panic attacks, or a return to school and friends. But for some, the very drugs meant to help can trigger something dangerous: new or worsening suicidal thoughts. This isn’t rare. It’s a known risk, documented by the FDA since 2004 and reinforced by every major child psychiatry guideline since. The truth is, psychiatric medications in adolescents require constant, careful monitoring - not just for side effects like weight gain or sleepiness, but for the quiet, creeping signs of hopelessness that can turn deadly.

Why Teens Are Different

Adults and teens don’t react the same way to psychiatric drugs. A medication that calms an adult’s depression might, in a teenager, create agitation, restlessness, or emotional numbness - all red flags for rising suicide risk. The brain is still developing. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for impulse control and long-term thinking, isn’t fully online until the mid-20s. So when a drug alters serotonin or dopamine levels, the teenage brain doesn’t always adjust smoothly. The result? A spike in suicidal ideation, especially in the first 1 to 4 weeks after starting a new medication or changing the dose.This isn’t theoretical. Studies show that adolescents on antidepressants have a 2 to 3 times higher risk of suicidal thoughts in the early treatment phase compared to those on placebo. The FDA’s black box warning isn’t just a legal footnote - it’s a life-saving alert. And it applies to more than just antidepressants. Antipsychotics, stimulants, even mood stabilizers can carry this risk, especially in kids with a history of self-harm, trauma, or family suicide.

What to Watch For: The Real Signs

Suicidal ideation doesn’t always come with a note or a dramatic statement. Often, it’s quiet. It’s the teen who used to text daily but now goes silent for days. It’s the sudden shift from crying to calm - not peace, but emptiness. It’s saying things like, “It doesn’t matter anymore,” or “Everyone would be better off without me,” even if they smile while saying it.Clinicians look for these specific changes:

- New or worsening agitation, irritability, or panic attacks

- Increased social withdrawal - skipping school, avoiding family, deleting social media

- Sudden improvement in mood that feels “off” - like they’ve made a decision and are now at peace with it

- Talking about death, dying, or suicide, even in a joking tone

- Giving away prized possessions or saying goodbye in unusual ways

- Increased substance use - alcohol, vaping, marijuana - often used to numb emotional pain

Parents and teachers are often the first to notice. A teacher might say, “They used to raise their hand. Now they stare at the wall.” A parent might notice their child has started sleeping all day, or worse - sleeps less but doesn’t seem tired. These aren’t just mood swings. They’re warning signs.

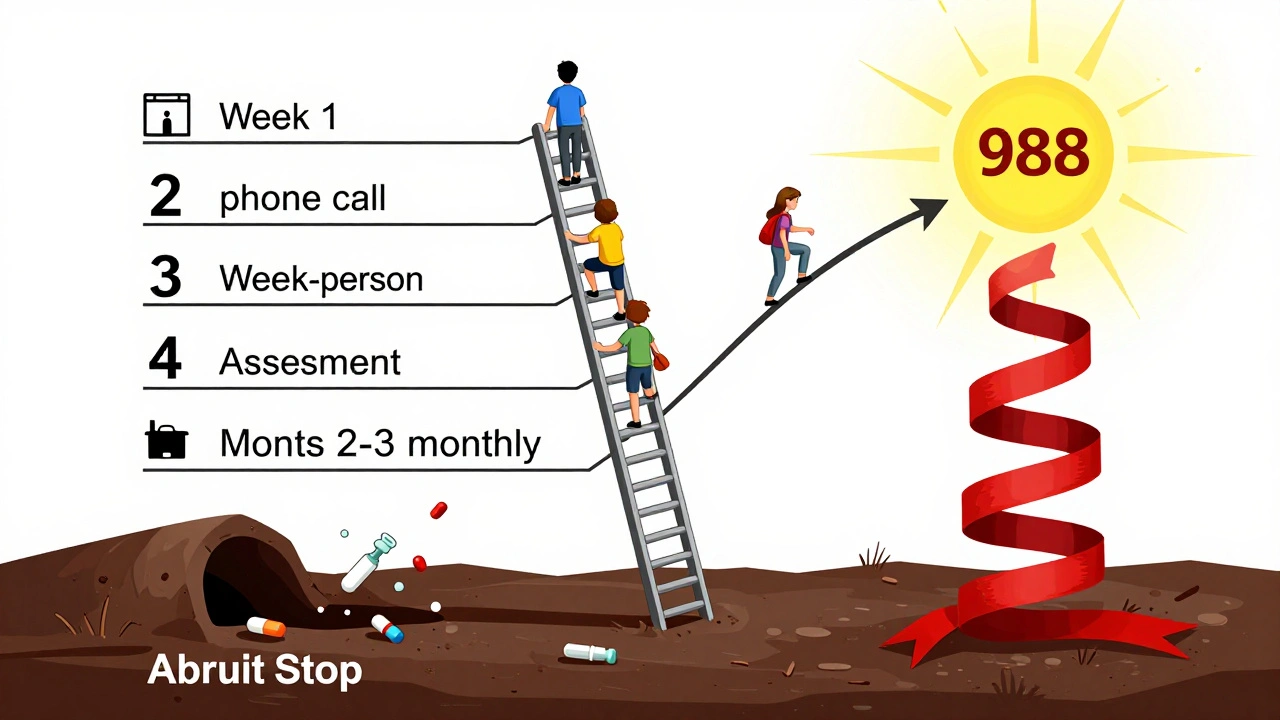

The Monitoring Protocol: When, How Often, and Who

There’s no one-size-fits-all schedule, but guidelines from California, New York, and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) agree on this: the first month is critical.For a teen starting an antidepressant or antipsychotic:

- Week 1: Check in by phone or video. Ask directly: “Have you had any thoughts about not wanting to be alive?” Don’t tiptoe. Use the word “suicide.” It doesn’t plant the idea - it opens the door.

- Week 2: In-person visit. Review sleep, appetite, energy, and mood. Ask about school, friends, and what they think of the medication. “Do you feel any different? Better? Worse? Numb?”

- Week 4: Full clinical assessment. Document everything - mood scales, behavior notes, family input. If there’s any concern, schedule a follow-up in 7 days, not 4 weeks.

- Months 2-3: Monthly visits. Continue asking about suicidal thoughts. Even if they seem stable, don’t assume safety.

- During dose changes or discontinuation: Increase visits to weekly. Stopping a medication can be just as risky as starting it. Withdrawal can trigger rebound depression or anxiety, and teens may feel trapped if they think they’ve lost their only coping tool.

It’s not just the psychiatrist’s job. School counselors, primary care doctors, and even coaches need to be informed - with consent - so they know what to watch for. A teen might never say anything to their doctor but might confide in a teacher. Communication between home, school, and clinic isn’t optional. It’s essential.

The Consent Conversation: You Need to Have It

Too often, parents sign forms without fully understanding the risks. A 2021 AACAP survey found that 42% of child psychiatry fellows felt they hadn’t been trained well enough to explain suicide risk during consent. That’s unacceptable.Before prescribing, the clinician must say clearly:

- “This medication can sometimes cause new or worse thoughts about suicide, especially in the first few weeks.”

- “This doesn’t mean your child will try to hurt themselves - but we need to watch closely.”

- “If you notice any of these signs - silence, withdrawal, talking about death - call us immediately. Don’t wait for the next appointment.”

- “We will check in every week at first. You are not alone in this.”

It’s not about scaring families. It’s about preparing them. When parents understand the risk and the plan, they become the most powerful safety net.

What If the Medication Isn’t Working - Or Is Making Things Worse?

Sometimes, the medication just doesn’t fit. Maybe it’s the wrong drug. Maybe the dose is too high. Maybe the teen needs therapy first, not pills. Or maybe, the medication is helping - but not enough.Here’s what not to do: stop it cold turkey. Abruptly stopping SSRIs or antipsychotics can cause severe withdrawal - nausea, dizziness, nightmares, and yes, a spike in suicidal thoughts.

Instead:

- Work with the prescriber to slowly taper the dose over weeks or months.

- Never discontinue without a plan for what comes next - therapy, lifestyle changes, or a different medication.

- Monitor even more closely during tapering. The risk doesn’t disappear when the pill stops.

And if the teen says, “I feel worse on this,” believe them. Don’t dismiss it as “adjustment.” Don’t say, “It takes time.” Time is not the issue - safety is.

What’s Missing in Most Clinics

Despite all the guidelines, most practices still don’t have real systems in place. A 2020 study found only 57% of outpatient child psychiatry clinics had standardized protocols for monitoring suicidal ideation tied to medication. In some states, it’s barely tracked at all.What’s missing?

- Structured screening tools used at every visit - not just once at intake

- Electronic alerts in medical records that flag high-risk patients

- Training for nurses and medical assistants to ask about suicidal thoughts

- Clear pathways to emergency care if risk is high

Some clinics are using digital tools - apps that let teens anonymously report mood changes daily. But only 19% of these tools are designed specifically to track medication-related suicidal ideation. Most are generic. That’s not enough.

The Bigger Picture: Medication Isn’t the Only Answer

Psychiatric meds can be life-saving. But they’re not magic. And they’re not always necessary. For many teens, therapy - especially CBT or DBT - works better than pills, especially when suicidal thoughts are tied to trauma, bullying, or family conflict.Best practice? Start with therapy. Add medication only if symptoms are severe, persistent, or putting the teen in danger. And never use medication as a quick fix for behavioral problems at school. That’s not treatment. That’s control.

The goal isn’t to make the teen quiet or compliant. It’s to help them feel like they have a future.

What Families Can Do Right Now

If your teen is on psychiatric medication:- Ask the doctor for a written monitoring plan - not just a verbal summary.

- Keep a simple journal: mood, sleep, energy, any new thoughts about death or suicide.

- Know the emergency number for the prescribing clinic. Save it in your phone.

- Remove access to lethal means - guns, medications, sharp objects, high places.

- Don’t wait for the next appointment if something feels wrong. Call now.

You are not overreacting. You are protecting your child.

Where the System Is Improving

California and New York now require detailed documentation of suicidal ideation checks in every teen’s medical record. The AACAP is updating its guidelines to make monitoring mandatory for all psychiatric meds - not just antidepressants. The National Institute of Mental Health is funding research to find biological markers that predict suicide risk, so we can identify who’s most vulnerable before it’s too late.Progress is slow. But it’s real.

Can psychiatric medications cause suicidal thoughts in teens?

Yes. Antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other psychiatric medications can increase the risk of suicidal thinking in adolescents, especially during the first few weeks of treatment or after a dose change. This is why the FDA requires a black box warning on these drugs for patients under 24. It doesn’t mean every teen will have these thoughts - but the risk is real enough that close monitoring is required by law and medical guidelines.

How often should a teen on psychiatric medication be checked for suicidal ideation?

In the first month, check-ins should happen weekly - especially after starting a new drug or changing the dose. After that, monthly visits are standard, but if there’s any concern, go back to weekly. During tapering or discontinuation, increase visits again. The first 4 weeks are the highest risk period.

What should parents do if their teen talks about suicide?

Take it seriously - always. Don’t argue, dismiss, or panic. Say, “I’m here. Let’s talk.” Then call the prescribing clinician immediately. If they’re unavailable, go to the nearest emergency room or call 988 (the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline). Remove access to weapons, pills, or other means of self-harm. Never leave a high-risk teen alone.

Is it safe to stop psychiatric medication if suicidal thoughts appear?

Never stop abruptly. Stopping suddenly can cause withdrawal symptoms that worsen depression or trigger intense suicidal thoughts. Always work with the prescriber to taper the dose slowly over weeks or months, while increasing monitoring. Have a plan for what comes next - whether that’s therapy, a different medication, or lifestyle changes.

Are there alternatives to medication for teens with suicidal ideation?

Yes. For many teens, therapy - especially cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) - is the first-line treatment. Family therapy, school support, and addressing social stressors like bullying or isolation can be more effective than medication alone. Medication should be considered when symptoms are severe, persistent, or pose immediate danger - not as a first resort for behavioral issues.

Why do some clinics not monitor for suicidal ideation properly?

Many clinics are under-resourced, understaffed, or lack standardized protocols. Some providers aren’t trained to ask about suicide risk directly. Others feel pressured to see patients quickly due to insurance constraints. A 2021 survey found only 34% of child psychiatry residents received adequate training in monitoring medication-related suicide risk. This gap is being addressed, but change is slow.

Monitoring for suicidal ideation isn’t about fear. It’s about care. It’s about showing up - consistently, courageously, and without judgment - when a teen is in the dark. The right medication, paired with the right monitoring, can turn a life around. But without vigilance, even the best treatment can fail. The goal isn’t to avoid medication. It’s to use it wisely - and never stop watching.

Eddie Bennett December 10, 2025

Been there. My little sister started on an SSRI last year and went quiet for two weeks-no texts, no laughs, just staring at the wall. We caught it early because we were watching. Not because we’re paranoid, but because the doctor told us exactly what to look for. That checklist in the post? Print it. Tape it to the fridge.

Sylvia Frenzel December 12, 2025

This is why I don’t trust psychiatrists. They push pills like candy and then act shocked when kids break. If you asked me, we’d stop medicating teens like lab rats and fix the damn system instead-schools, family pressure, social media. But no, easier to slap on a black box warning and call it a day.

Paul Dixon December 13, 2025

My cousin was on an antipsychotic for psychosis and started talking like he’d already checked out of life. We didn’t realize it was the meds until his mom called the doc on day 17. He cried and said, ‘I just didn’t feel anything anymore.’ That’s not calm. That’s numb. And yeah, it’s terrifying. Glad someone’s laying it out like this.

Vivian Amadi December 13, 2025

Stop pretending meds are safe. They’re chemical restraints with a side of suicide risk. If your kid’s not screaming bloody murder, you’re not paying attention. And don’t tell me ‘it takes time’-time is the enemy here. I’ve seen too many kids disappear after a script was written. Wake up.

Lisa Stringfellow December 15, 2025

So what? You’re telling me we’re supposed to monitor every kid on every pill like they’re ticking bombs? What about the ones who don’t have parents who care? Or schools that don’t care? Or doctors who are overworked? This post reads like a PSA from a perfect world. In reality, we’re just scrambling to keep kids alive between insurance denials and 10-minute appointments.

Kristi Pope December 17, 2025

Love this breakdown. Seriously. The part about ‘sudden calm’? That hit me in the chest. My nephew went from crying every night to smiling and saying ‘I’m fine’-and I thought he was healing. Turns out he’d made a plan. We got him help in time because I remembered reading something like this last year. Don’t wait for the perfect moment to act. Act now. Call now. Even if it’s 2am.

Aman deep December 18, 2025

from india here… we dont talk about this enough. my cousin took sertraline and became quiet like a ghost. family said ‘he’s just shy’… but he was gone inside. i wish someone told us about the 1-4 week window. now i tell every parent i know: ask directly. say ‘suicide’. dont be scared. silence kills faster than any pill.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt December 20, 2025

It’s not about whether meds are good or bad. It’s about whether we’re willing to show up. The real tragedy isn’t the medication-it’s the silence that follows. We treat mental health like a problem to be fixed, not a person to be held. The checklist matters. The calls matter. The ‘I’m here’ matters more than the script.

Ariel Nichole December 20, 2025

My daughter’s on bupropion. We do weekly check-ins. I keep a little notebook. She knows I’m not judging, just watching. She says it helps her feel seen. That’s the whole point, right? Not to fix her-but to be with her while she figures it out.

john damon December 22, 2025

bro i just want to say thank you for this post 🙏 i was about to quit my kid’s meds after 3 days because she got ‘weird’… then i read this. we’re doing the weekly check-ins now. she’s still quiet but she smiled at me today. small wins.

matthew dendle December 23, 2025

lol so now we gotta babysit teens on antidepressants like they’re toddlers with a gun? next thing you know we’ll be fingerprinting them before they get a zoloft prescription. just let them grow up. some kids are just moody. not every cry for help needs a pill or a panic button.

Monica Evan December 24, 2025

as a school nurse i see this every week. a kid stops coming to lunch. stops answering texts. says ‘im fine’ with zero eye contact. we dont have a protocol. no alerts. no training. just me and a clipboard hoping i catch it before its too late. this needs to be mandatory. not optional. not nice to have. mandatory.

Taylor Dressler December 25, 2025

The FDA’s black box warning has been around for 20 years. Why are we still acting surprised? This isn’t new information. It’s systemic neglect. Clinics need standardized screening tools, mandatory training for all staff, and electronic alerts. This isn’t about blame-it’s about building systems that don’t rely on individual heroism to keep kids alive.

Aidan Stacey December 26, 2025

I used to think meds were the answer. Then I watched my brother go from laughing to vacant in 11 days. We didn’t know what to do. No one told us to look for the quiet. Now I volunteer at a teen crisis center. I tell every parent: don’t wait for a crisis. Watch the silence. It’s louder than any scream.