Why Dialysis Access Matters More Than You Think

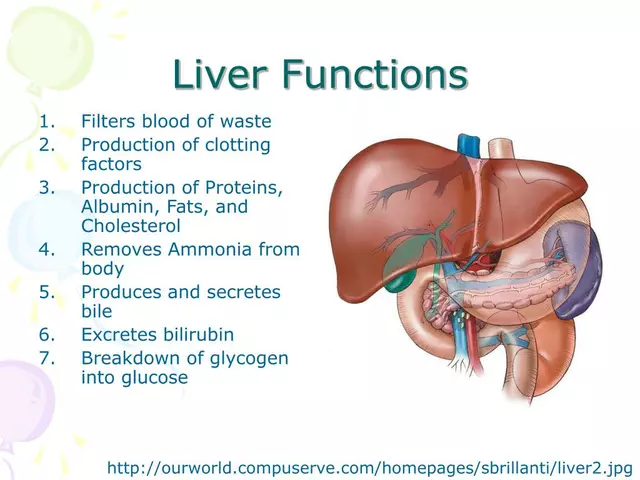

If you’re on hemodialysis, your access point isn’t just a tube or a needle site-it’s your lifeline. Every time you sit down for treatment, your blood flows through this connection to be cleaned by the machine. And the type of access you have can mean the difference between months of complications and years of stable, independent care.

There are three main types: arteriovenous (AV) fistulas, AV grafts, and central venous catheters. Each has its own pros, cons, and care routines. But here’s the hard truth: AV fistulas are the gold standard for a reason. They last longer, cause fewer infections, and save lives. The National Kidney Foundation and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have spent decades pushing for fistulas as the first choice-and the data backs them up.

Patients using catheters have a 53% higher risk of dying from complications than those with fistulas. That’s not a small gap. It’s life or death. And yet, too many people still end up with catheters as their long-term solution-not because it’s better, but because they didn’t get the right prep, or their veins weren’t checked early enough.

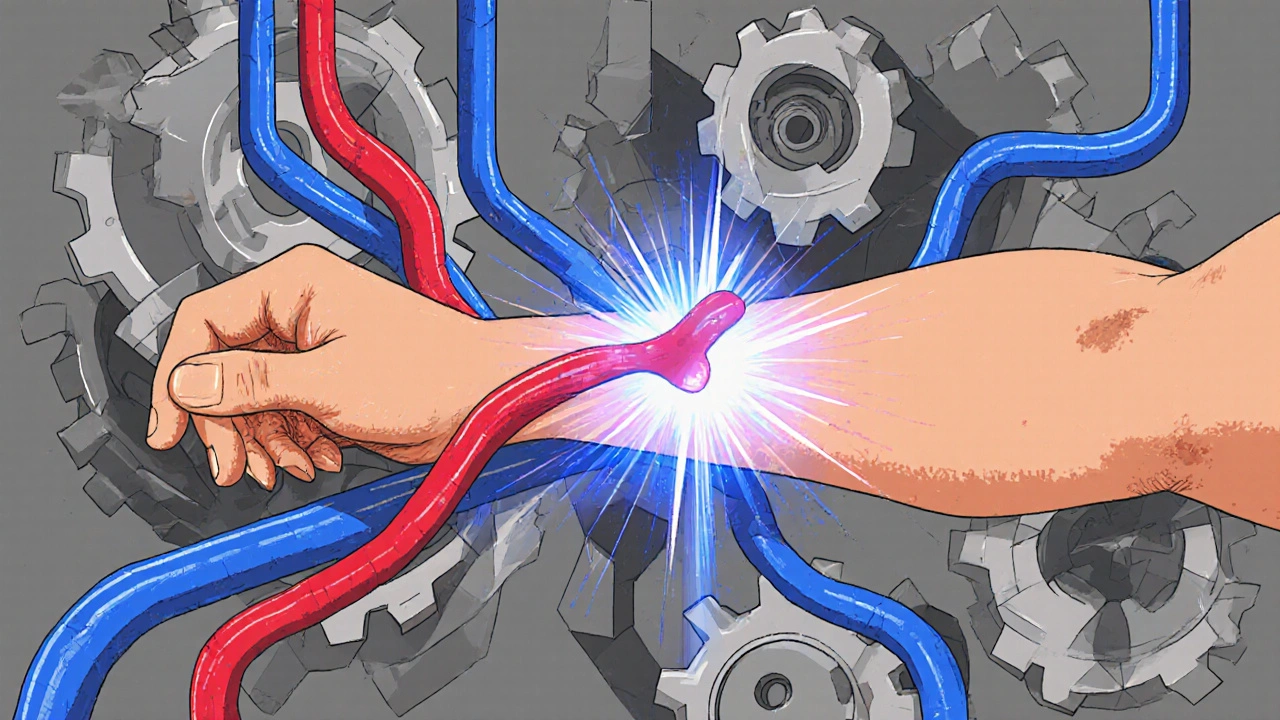

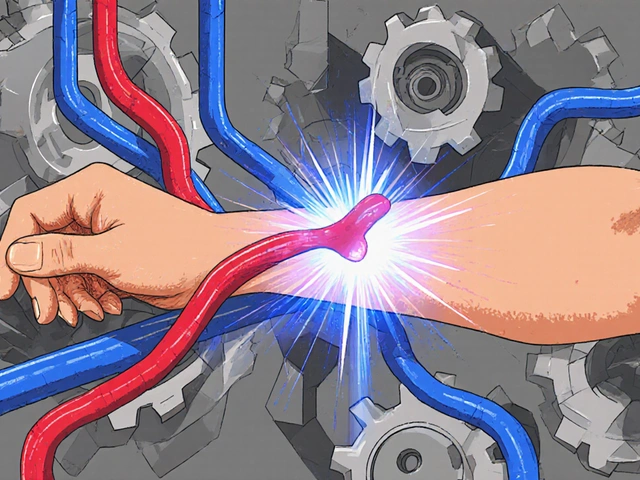

AV Fistula: The Gold Standard

An AV fistula is made by surgically connecting an artery directly to a vein, usually in your forearm. This isn’t a quick fix. It takes 6 to 8 weeks for the vein to grow stronger and wider-this is called maturation. During that time, your vein thickens to handle the high blood flow needed for dialysis. Once mature, it can last for decades.

Why is it so good? Because it’s made from your own tissue. No foreign material means less chance of infection or clotting. Patients who’ve had fistulas for 5, 7, even 10 years often say they barely think about them. They can shower normally, sleep on that arm, and don’t need daily cleaning routines like catheter users do.

But it’s not perfect. About 30-60% of fistulas don’t mature properly, especially in older adults or those with diabetes. That’s why vein mapping-a simple ultrasound scan-is critical before surgery. It checks if your veins are strong enough to support a fistula. If they’re too small or blocked, your doctor might suggest a graft instead.

Once your fistula is working, you need to check it daily. Feel for a vibration-the “thrill.” That’s your blood rushing through. If it disappears, or if you notice swelling, pain, or a change in color, call your care team immediately. Clots can form fast.

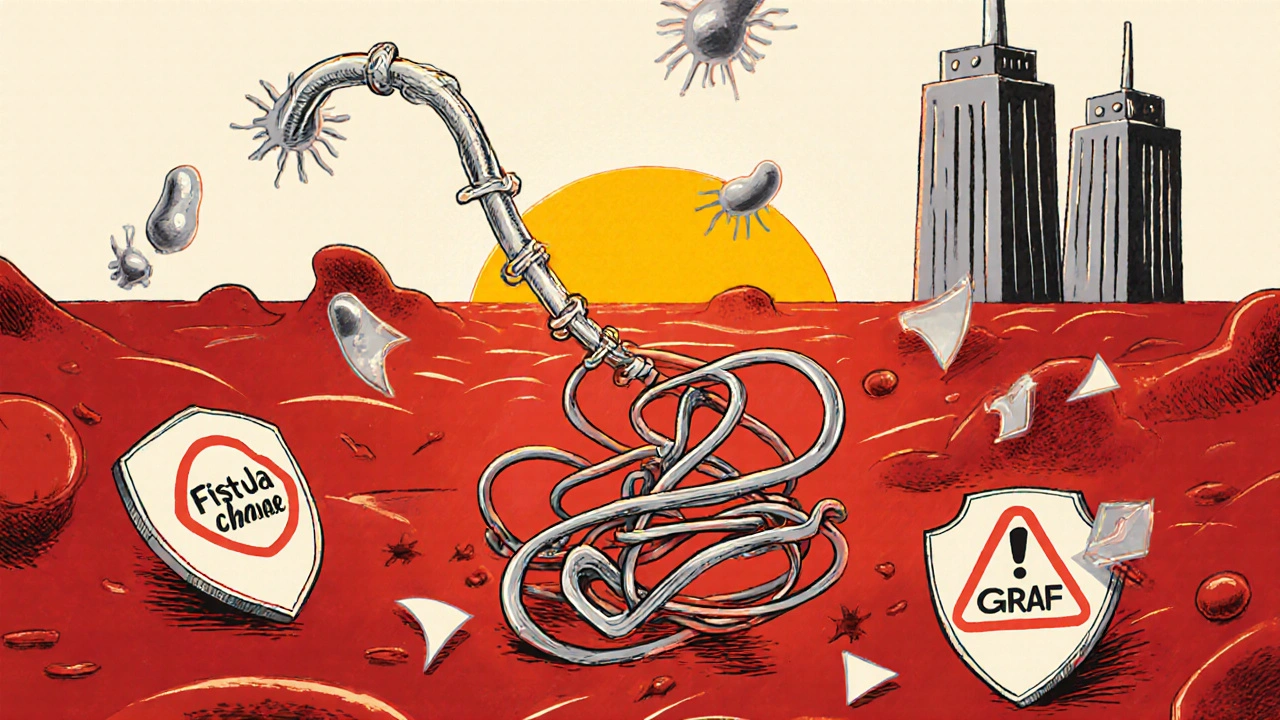

AV Grafts: The Backup Plan

When your veins aren’t strong enough for a fistula, an AV graft is the next best option. Instead of connecting artery to vein directly, a soft synthetic tube-usually made of PTFE-is surgically placed between them. This tube acts like a bridge. And because it’s artificial, it can be used much sooner: just 2 to 3 weeks after surgery.

That speed is a big advantage. But grafts come with trade-offs. They’re more likely to clot or get infected than fistulas. About 30-50% of grafts need at least one procedure in the first year to fix a blockage. These interventions-like balloon angioplasty or stent placement-are common, but they add up. Over time, grafts may need replacing every 2-3 years.

Patients often describe grafts as “high-maintenance.” You still need to check for the thrill, but you also have to be extra careful with needle placement. The graft material is softer than your natural vein, so repeated needle sticks can cause bulges called aneurysms. These aren’t always dangerous, but they increase the risk of bleeding or infection.

Still, for many people, a graft is the only realistic path to long-term dialysis access. It’s not ideal, but it’s reliable. And with better materials being developed-like Humacyte’s bioengineered vessels in clinical trials-it may get even better soon.

Central Venous Catheters: Temporary, But Often Permanent

Catheters are the fastest option. A soft tube is inserted into a large vein in your neck, chest, or groin. You can start dialysis the same day. That’s why they’re often used in emergencies. But here’s the problem: they’re meant to be temporary. And too often, they become permanent.

Catheters are the riskiest access type. They carry a 2.1 times higher risk of fatal infection than fistulas. Every time you shower, you have to cover the site. Sleeping on it? Not safe. Moving around? Risk of pulling it out. And because it’s sitting in a major vein, it’s a direct path for bacteria to enter your bloodstream.

One patient in Perth told me she had to skip her favorite swimming routine for years because of her catheter. Another said he missed two weeks of work after a catheter-related infection landed him in the hospital. These aren’t rare stories. The rate of bloodstream infections from catheters is 0.6 to 1.0 per 1,000 catheter days. That means if you’re on dialysis three times a week, your risk adds up fast.

Catheter care is intense. You need sterile technique for every dressing change. Your care team will train you, but even then, mistakes happen. And if you forget to clean it? You could end up with sepsis.

That’s why experts push so hard to get people off catheters as soon as possible. If you’re on one now, ask: “Can I get a fistula or graft?” Even if you’ve been on a catheter for months, it’s not too late to switch.

What You Can Do to Protect Your Access

Your access doesn’t take care of itself. But you can do a lot to keep it healthy.

- Check daily: Feel for the thrill in your fistula or graft. Listen for a whooshing sound with a stethoscope if you have one. No thrill? Call your clinic.

- Don’t sleep on your access arm: Avoid tight clothing, watches, or bags on that side.

- Keep it clean: Wash your access site with soap and water before every dialysis session. Never pick at scabs or scratch the skin.

- Report changes: Redness, swelling, warmth, pain, or discharge? Don’t wait. Call your nurse right away.

- Ask about vein mapping: If you’re starting dialysis soon, insist on an ultrasound scan of your arms before surgery. It’s quick, painless, and can save you from a failed fistula.

And don’t underestimate education. Patients who get proper training before their first surgery have 25% fewer complications in their first year. That’s huge. Ask for a one-on-one session with a dialysis nurse. Bring a family member. Take notes.

Why Some People Still Get Catheters-And What’s Being Done

It’s not just about medical need. There are systemic issues too.

Black patients are 30% less likely to get fistulas than White patients-even when their health status is the same. Why? Access to specialists, delays in referrals, or assumptions about vein quality. These disparities are real, and they cost lives.

There’s also the problem of timing. Many patients start dialysis without any access planned. They end up with a catheter out of necessity. But now, hospitals are changing. The Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative, launched in 2003, pushed fistula rates from 32% to 61% in just seven years. Today, nearly two-thirds of long-term dialysis patients use fistulas.

New tech is helping too. In 2022, the FDA approved Vasc-Alert, a wireless sensor that monitors fistula blood flow. It sends alerts to your phone if flow drops, catching clots before they cause problems. Clinical trials showed a 20% drop in clotting events.

And there’s hope on the horizon: bioengineered vessels that could replace synthetic grafts. They’re still in trials, but early results show they’re less likely to clot. For patients with no good veins, this could be a game-changer.

What’s Next for You?

If you’re new to dialysis, talk to your nephrologist now. Ask: “What’s my best access option?” Push for vein mapping. Don’t accept a catheter as your only choice.

If you already have a fistula or graft, keep up with your checks. Don’t skip appointments. If your access isn’t working well, don’t wait. There are more options than you think.

If you’re on a catheter, ask your team: “What’s my plan to get off this?” Even if you’ve been on it for months, switching to a fistula or graft is still possible-and worth it.

Dialysis access isn’t just a medical procedure. It’s about your freedom, your safety, and your future. Choose wisely. Advocate for yourself. And remember: your body is doing hard work every day. The least you can do is protect the connection that keeps you alive.

Melanie Taylor November 14, 2025

This post literally made me cry 😭 I’ve been on dialysis for 6 years now-fistula since day 2. My mom taught me to check the thrill every morning before coffee. It’s not just medical advice-it’s a ritual. Thank you for saying what so many of us live every day. ❤️

Teresa Smith November 15, 2025

The systemic disparities in access to AV fistulas are not merely statistical-they are moral failures. The fact that Black patients are 30% less likely to receive optimal care despite identical clinical profiles reflects entrenched inequities in healthcare delivery. This is not about individual choice; it is about institutional neglect. Advocacy must be structural, not supplemental.

Danish dan iwan Adventure November 15, 2025

Fistula maturation failure rates are 30–60% due to endothelial dysfunction in diabetic microangiopathy. Graft patency is compromised by neointimal hyperplasia at anastomotic sites. Catheter-related bacteremia stems from biofilm formation on polyurethane surfaces. Stop romanticizing. This is vascular pathology, not a lifestyle blog.

David Rooksby November 17, 2025

Okay but have you ever heard about the secret government program that replaces dialysis access data with fake stats to make hospitals look good? I know a guy whose cousin’s neighbor works at the CDC and he said they’re hiding the real infection numbers because Medicare doesn’t want to pay for better grafts. Also, the FDA approved Vasc-Alert? That’s just a cover for the same old tech rep who’s been pushing it since 2015. They’re all in on it. And why is everyone so quiet about how the dialysis machines are secretly powered by alien tech? I’ve seen the wiring-it’s not copper. It’s... something else.

ZAK SCHADER November 18, 2025

Fistulas are great if you got time and money. But most people in this country don’t. Catheters are faster, cheaper, and get the job done. Stop acting like everyone’s got a specialist on speed dial. We got bills to pay, jobs to keep, and kids to feed. Stop guilt-tripping folks who just want to survive another day.

Oyejobi Olufemi November 18, 2025

You speak of 'life or death' as if it were a moral imperative... but have you considered that death itself is merely a biological endpoint? The body is a machine, and machines fail. To fetishize the fistula is to worship the illusion of control. We are all temporary conduits-catheters, grafts, fistulas-merely different pathways to entropy. Your vigilance, your thrill-checking, your sterile routines... all are desperate rituals against the inevitable. And yet, you cling to them. Why? Because you fear the silence that follows the last heartbeat. But silence is not failure. It is completion.

Ankit Right-hand for this but 2 qty HK 21 November 20, 2025

This whole 'fistula first' campaign is just another Western capitalist scam to sell more surgeries. In India, we use catheters for 80% of cases and still live longer than your people. You think your fancy ultrasound mapping is better? My uncle did dialysis for 12 years with a catheter and never got sick once. He drank beer every night. You don't need fancy tech-you need discipline. And maybe less whining.

Dan Angles November 20, 2025

Thank you for the comprehensive breakdown. As a nephrology nurse for 18 years, I’ve seen too many patients transition from catheters to fistulas after years of avoidable complications. The data is unequivocal. What’s missing from public discourse is the human cost of delay: lost work, emotional trauma, family strain. We must institutionalize early referral and vascular access planning as standard of care-not privilege. This isn’t advocacy. It’s ethics.