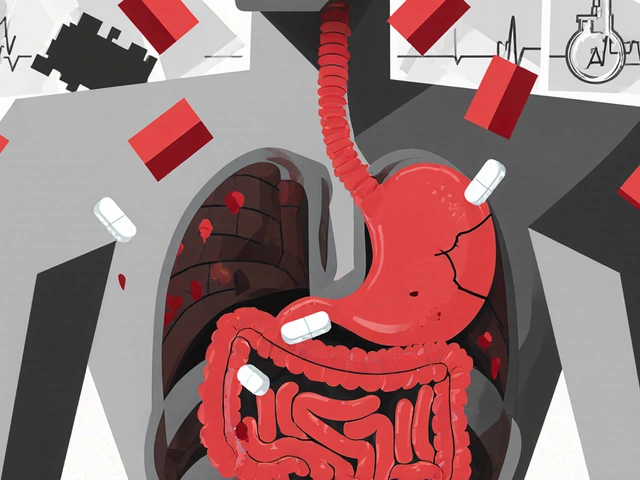

Every time someone takes a new medicine, there’s a hidden system working behind the scenes to watch for problems. This isn’t science fiction-it’s pharmacovigilance, the global network that tracks side effects, dangerous interactions, and unexpected reactions to medicines after they’ve reached millions of people. Without it, we wouldn’t know about the increased risk of dengue hemorrhagic fever after the Dengvaxia vaccine, or why certain antibiotics cause rare but deadly skin reactions in specific populations. These systems don’t just react-they prevent harm before it spreads.

How the Global Drug Safety Network Works

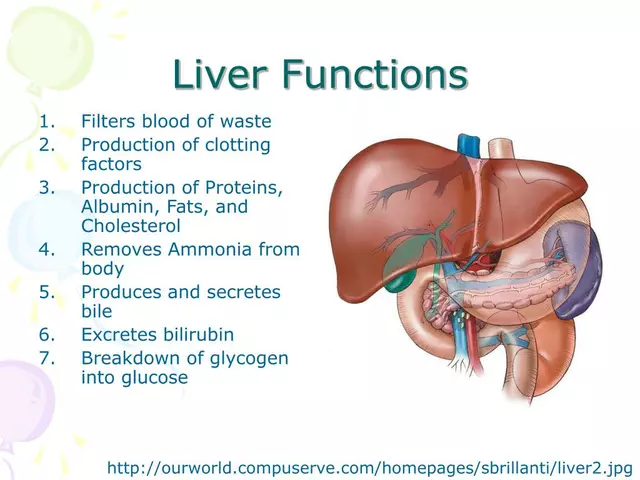

The backbone of international drug safety monitoring is the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring (PIDM), a global network established in 1968 after a resolution by the World Health Assembly called for systematic tracking of adverse drug reactions. It’s not a single database run by one country-it’s a coalition of 170+ national health agencies sharing data through a central hub: VigiBase, the world’s largest repository of individual case safety reports, managed by the Uppsala Monitoring Centre in Sweden. As of 2023, it held over 35 million reports, up from just 5 million in 2012.Each report, called an Individual Case Safety Report (ICSR), comes from doctors, pharmacists, patients, or pharmaceutical companies. They describe what drug was taken, what side effect occurred, when, and how severe. To make sense of this chaos, every report is standardized using MedDRA, a medical terminology system with over 78,000 standardized terms organized into 27 categories like "skin disorders" or "nervous system disorders". Drugs are coded using WHODrug Global, a dictionary with more than 300,000 medicine names across 60+ therapeutic classes. This ensures that "aspirin" in Japan, "acetylsalicylic acid" in Germany, and "Bayer" in the U.S. all get tagged the same way.

Reports flow in electronically using the E2B(R3), an international standard format developed by the International Council for Harmonisation for transmitting safety data. Countries use different tools to collect this data-some rely on paper forms, others on apps or integrated electronic health records. The Pharmacovigilance Monitoring System (PViMS), a web-based tool developed by MTaPS, lets clinics in low-resource settings report events in real time.

Regional Systems: EU, U.S., and Beyond

While WHO’s system is global, powerful regional networks operate with more authority and speed. The European Union’s EudraVigilance, a system managed by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), handles around 1.2 million reports per year. Unlike WHO, which collects data voluntarily, the EU legally requires drug companies to submit adverse event reports within 15 days. It’s also faster: 92% of safety signals are assessed within 75 days thanks to the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC), a panel of experts mandated to review urgent safety issues within 60 days.The U.S. FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), processes roughly 2 million reports annually. It’s independent of WHO’s system but still contributes data to VigiBase. The FDA doesn’t require electronic submissions as strictly as the EU, so many reports still come in via fax or mail. Still, FAERS has helped identify risks like the link between certain diabetes drugs and pancreatitis, leading to updated warnings.

Meanwhile, countries like the UK use their own systems-like the Yellow Card Scheme, which collects over 100,000 reports yearly and is used by 78% of healthcare professionals via a mobile app. Australia’s TGA has a similar system, and Canada’s MedEffect program has seen a 40% increase in reporting since launching its online portal in 2020.

The Data Gap: Rich Countries vs. Poor Countries

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: the world’s drug safety system is skewed. High-income countries, which make up just 16% of the global population, submit 85% of all reports to VigiBase. Sweden reports about 1,200 adverse events per 100,000 people each year. Nigeria? Just 2.3 per 100,000. That doesn’t mean Nigerians don’t have side effects-it means they don’t have the systems to report them.A WHO assessment of 50 African nations found that only 18 had dedicated pharmacovigilance budgets. On average, low-income countries spend $0.02 per person on drug safety monitoring. High-income countries spend $1.20-60 times more. Many clinics in rural areas still use paper forms. Internet access is spotty. Staff are overworked and undertrained. A 2022 survey in Southeast Asia found 68% of pharmacovigilance officers had received less than 15 hours of formal training, even though WHO recommends 40 hours.

But change is happening. Ethiopia cut its reporting time from 90 days to 14 after adopting PViMS. Since 2020, 45 low- and middle-income countries have started using digital tools for vaccine safety monitoring, slashing data transmission time from two months to just seven days. Zanzibar joined the WHO network in January 2024. Ukraine reactivated its national center in March 2023 after the war disrupted operations. These aren’t just technical upgrades-they’re lifelines.

How AI Is Changing the Game

With over 35 million reports and counting, no human can read them all. That’s where artificial intelligence comes in. The Uppsala Monitoring Centre now uses AI to scan VigiBase for unusual patterns. One 2023 study showed their AI system cut false positive signals by 28% compared to older methods. Instead of sifting through thousands of unrelated reports, analysts now focus on the ones that actually matter.AI doesn’t replace experts-it helps them. It can spot a rare liver injury linked to a new diabetes drug in Brazil that’s also showing up in Colombia and Indonesia. Without AI, those connections might take years to notice. With it, signals emerge in weeks. The EU is doing something similar: using electronic health records from 150 million patients to catch safety issues earlier than spontaneous reports ever could. That’s improved signal detection sensitivity by 37%.

Why This Matters to You

You might think, "I’m not a doctor. I don’t work in pharma. Why should I care?" But here’s the thing: drug safety monitoring protects you every time you pick up a prescription, buy an over-the-counter painkiller, or get a vaccine. It’s why the label on your medication says "may cause dizziness" or "do not use if pregnant." It’s why some drugs get pulled from shelves, and others get new warnings added.When you report a side effect-even if you’re not sure it’s related-you’re adding to a global safety net. In 2022, a patient in Canada reported unusual bleeding after taking a new blood thinner. That report, combined with others, led to a revised warning that likely prevented dozens of serious incidents. You don’t need to be an expert to make a difference.

The Future: Standardization and Sustainability

By 2025, the world will adopt the ISO IDMP, a new set of standards that will uniquely identify every medicine using over 100 data points-from chemical structure to packaging. This means if a drug is sold under 12 different brand names in 8 countries, systems will know it’s the same substance. That could improve cross-border data matching by 40%, making global signal detection far more accurate.But technology alone won’t fix everything. The biggest challenge isn’t software-it’s money and training. Only 28% of countries have a formal pharmacovigilance system. The rest rely on donors or temporary funding. Without long-term investment, these systems collapse when emergencies pass. The global pharmacovigilance market is growing fast-projected to hit $13 billion by 2030-but most of that money goes to big pharma and high-income nations. Low-income countries need sustained support, not just short-term grants.

Right now, 85% of WHO member countries have laws requiring drug safety reporting. That’s up from 65% in 2010. Progress is real. But real safety means everyone is seen, not just the loudest voices. The next big breakthrough won’t come from a new algorithm-it’ll come when a nurse in rural Malawi can report a reaction in five minutes, and someone in Sweden sees it and acts on it.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a scientist to help. If you or someone you know has an unexpected reaction to a medication:- Write down what drug was taken, the dose, when you started, and what happened.

- Check your country’s national reporting system-Australia’s TGA, the UK’s Yellow Card, or the FDA’s MedWatch.

- Submit the report. Even if you’re unsure, it matters.

- Encourage your doctor or pharmacist to report too.

Every report is a piece of the puzzle. Together, they keep medicines safer for everyone.

What is the main purpose of international drug safety monitoring?

The main purpose is to detect, assess, and prevent harmful side effects of medicines after they’ve been approved and used by the public. It ensures that the benefits of a drug continue to outweigh its risks throughout its life on the market, protecting patient safety and informing public health decisions.

How does VigiBase differ from EudraVigilance?

VigiBase is the global database managed by WHO, collecting voluntary reports from over 170 countries. EudraVigilance is the EU’s legally mandated system that requires drug companies to report adverse events within 15 days and has stricter timelines for reviewing safety signals. VigiBase has broader geographic coverage; EudraVigilance has faster processing and stronger regulatory power.

Why do high-income countries report more adverse drug reactions?

They have better infrastructure: trained staff, electronic reporting systems, public awareness campaigns, and funding. Low-income countries often lack basic resources like internet access, staff training, or even dedicated pharmacovigilance budgets. More reports don’t mean more side effects-they mean better reporting systems.

Can patients report adverse drug reactions themselves?

Yes. Many countries, including the U.S., UK, Australia, and Canada, allow patients to report side effects directly through online portals or apps. Your report can help identify new safety risks, even if you’re not a healthcare professional.

What role does AI play in drug safety monitoring?

AI helps analyze millions of reports to find unusual patterns that humans might miss. It reduces false alarms, speeds up signal detection, and highlights potential risks across countries. For example, AI helped identify early signs of a rare liver injury linked to a new diabetes drug across multiple regions within weeks.

What is the biggest challenge facing global drug safety systems today?

The biggest challenge is inequality. Most reporting comes from wealthy nations, leaving billions in low-income countries underrepresented. Without investment in training, infrastructure, and sustainable funding, these systems can’t protect everyone equally. Safety isn’t global unless it’s inclusive.

Angie Thompson January 26, 2026

This is wild 😍 I had no idea my weird stomach ache after that new pill was part of a global database with 35 MILLION reports. Like... I just thought I was unlucky. Turns out I’m part of a scientific lifeline. 🙌

James Nicoll January 27, 2026

So we’ve built this massive, expensive machine to catch side effects... but only rich people’s side effects count? Cool. Real cool. Next up: AI that only listens to English-speaking patients with insurance.

John Wippler January 27, 2026

This system is basically humanity’s immune system for medicine. We inject drugs into the population, then we have this vast neural net of doctors, apps, and patients monitoring for anomalies. It’s not perfect, but it’s the closest thing we have to collective wisdom in a world that’s obsessed with speed over safety. And yeah, it’s broken in the Global South-but that’s not a tech problem. It’s a moral one.

rasna saha January 29, 2026

In India, we still use paper forms in rural clinics. My aunt reported a reaction to her blood pressure med and waited 6 months for anyone to respond. But I’m glad someone’s finally talking about this. We need more people to report, even if it feels pointless.

Skye Kooyman January 29, 2026

So AI spots patterns faster now. Cool. But who decides what’s a 'pattern'? And why do we still let fax machines be part of the system in 2024?

Uche Okoro January 31, 2026

The structural underinvestment in pharmacovigilance infrastructure within low-income jurisdictions constitutes a profound epistemic injustice. The absence of standardized digital reporting frameworks, coupled with endemic under-resourcing, engenders a data vacuum that systematically obscures the pharmacological burden borne by marginalized populations. This is not merely a logistical deficit-it is a violation of the principle of distributive justice in global health equity.

shivam utkresth February 2, 2026

I love how this post doesn’t just say 'report side effects' but actually tells you how. My cousin in Delhi just used the MedEffect app after her mom got a rash from a generic antibiotic. Took 3 mins. That’s the kind of change that actually moves the needle.

Aurelie L. February 2, 2026

I reported my migraine after the flu shot. Nobody cared. So I posted about it on TikTok. Now 200 people are reporting too. Maybe that’s the real system.

bella nash February 3, 2026

The integrity of pharmacovigilance as a public health mechanism is predicated upon the uniformity of data acquisition protocols and the equitable distribution of reporting resources across sovereign jurisdictions. Any deviation from this paradigm constitutes a systemic failure in the duty of care owed to the global citizenry.

Betty Bomber February 4, 2026

I just took a new vitamin and my tongue feels weird. Should I report it? Or is that just... me?

Renia Pyles February 5, 2026

Oh great. Another article about how rich people’s complaints are the only ones that matter. Meanwhile, my cousin in Lagos died from a fake antibiotic and no one even logged it. This system is a luxury. Don’t pretend it’s justice.

Ashley Karanja February 6, 2026

I’ve been thinking about this for weeks. The fact that we can track a liver injury in Brazil, Colombia, AND Indonesia through AI patterns but still can’t get a nurse in Malawi to submit a report on a simple tablet... it’s heartbreaking. We have the tech. We have the knowledge. What we’re missing is the will. And that’s not a problem of algorithms-it’s a problem of humanity. I keep wondering if the next person who dies from an undetected reaction will be someone we love. And if we didn’t report because we thought it was ‘just one case,’ will we ever forgive ourselves?

Napoleon Huere February 7, 2026

The real revolution isn’t AI or E2B(R3). It’s when a kid in a village in Nepal learns that her mom’s reaction to a drug isn’t her fault-and that someone, somewhere, will listen. That’s the real safety net.

Aishah Bango February 9, 2026

If you don’t report side effects, you’re complicit. You think it’s no big deal? That’s how people die. Stop being lazy. Submit the form. It takes 2 minutes. Your apathy is killing people.