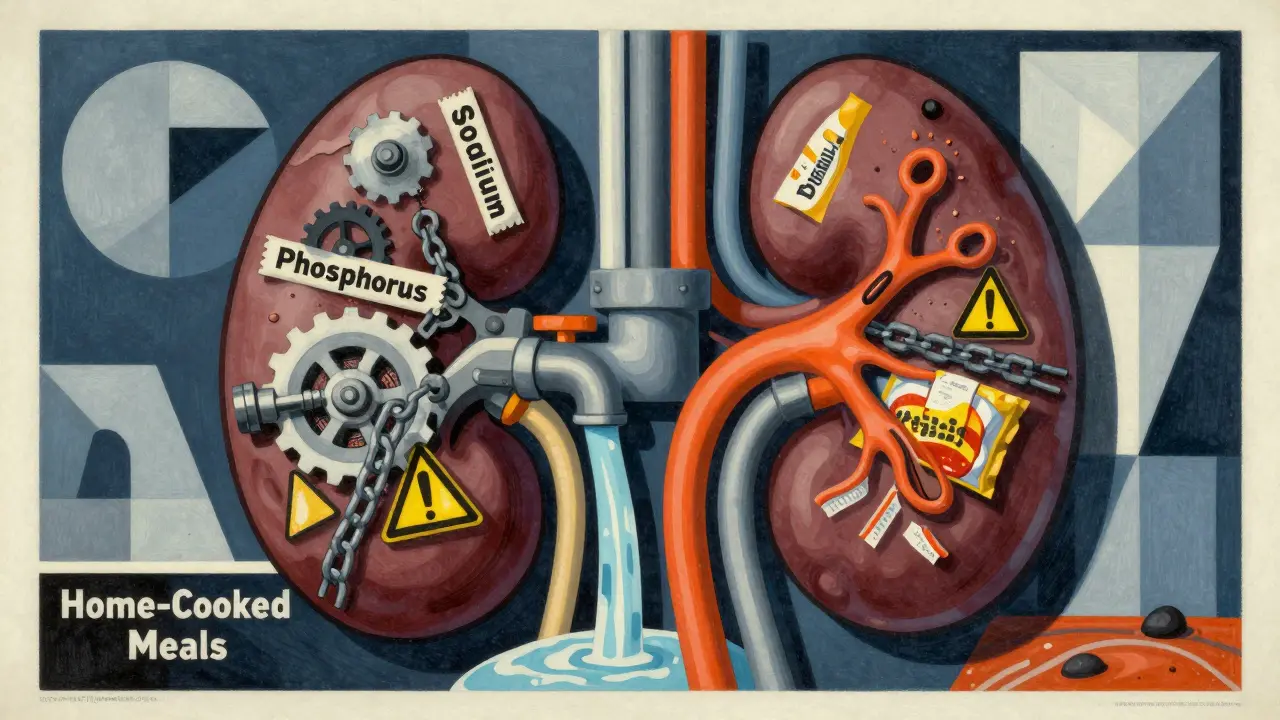

When your kidneys aren't working well, what you eat becomes just as important as any medication. A renal diet isn’t about losing weight or eating ‘clean’-it’s a medical tool to keep dangerous minerals from building up in your blood. Too much sodium, potassium, or phosphorus can cause swelling, heart problems, bone damage, and even sudden cardiac arrest in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The goal isn’t to eliminate these minerals entirely, but to keep them within safe limits so your kidneys don’t have to work overtime.

Why Sodium Matters More Than You Think

Sodium isn’t just about salty snacks. It’s hidden in almost every packaged food: bread, canned soup, deli meats, frozen meals, even breakfast cereal. For someone with CKD, too much sodium means your body holds onto water. That leads to high blood pressure, swollen ankles, shortness of breath, and extra strain on your heart. The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2023 guidelines recommend no more than 2,000-2,300 milligrams per day-roughly one teaspoon of salt. But most Americans eat over 3,400 mg daily.Here’s the hard truth: 75% of your sodium comes from processed and restaurant foods, not the salt shaker. A single serving of canned tomato soup can pack 800-1,200 mg. One slice of deli ham? Around 600 mg. That means if you eat two meals with packaged foods, you’ve already hit your daily limit.

How to cut back? Read labels. Look for “no salt added,” “low sodium,” or “unsalted.” Cook at home more often. Use herbs like oregano, basil, or garlic powder instead of salt. Mrs. Dash and similar herb blends are safe and flavorful. Cutting sodium by just 1,000 mg a day can lower systolic blood pressure by 5-6 mmHg, according to the CDC. That’s the same drop you’d see with some blood pressure meds.

Managing Potassium: The Silent Threat

Potassium helps your muscles and nerves work properly-but when your kidneys can’t filter it out, it builds up. Levels above 5.5 mEq/L can trigger dangerous heart rhythms, even without warning. Many people don’t feel symptoms until it’s too late.The National Kidney Foundation suggests keeping potassium under 2,000-3,000 mg per day for stage 3-5 CKD, but your doctor will adjust this based on your blood tests. Some foods are safe in small amounts. A medium apple has only 150 mg. Half a cup of cooked cabbage? Just 12 mg. Blueberries (½ cup) are around 65 mg. These can be part of your daily meals.

But many “healthy” foods are potassium bombs. One banana has 422 mg. An orange? 237 mg. A baked potato? Over 900 mg. Spinach, tomatoes, avocados, and dried fruit are also high. You don’t have to cut them out forever, but you need to limit portions and learn how to reduce their potassium content.

Leaching vegetables is a proven trick. Slice potatoes, carrots, or beets thin, soak them in warm water for 2-4 hours, then boil them in a large pot of fresh water. This can cut potassium by up to 50%, according to DaVita’s 2023 nutrition guide. Drain and rinse again after boiling. It’s extra work, but it lets you enjoy foods you love without risking your heart.

Also, pay attention to where potassium comes from. Animal-based foods like meat, dairy, and eggs absorb 80-90% of their potassium. Plant-based sources like beans and leafy greens absorb only 50-70%. That means you might be able to eat more plant foods safely-but still, portion control matters.

Phosphorus: The Hidden Killer in Processed Foods

Phosphorus is found naturally in protein-rich foods like meat, dairy, and beans. But here’s what most people don’t know: the real danger isn’t natural phosphorus-it’s the additives. Food manufacturers add phosphorus to processed foods to enhance flavor, texture, and shelf life. These additives are almost 100% absorbed by your body, compared to only 50-70% from natural sources.The KDOQI 2020 guidelines recommend keeping phosphorus under 800-1,000 mg per day for non-dialysis CKD patients. But a 12-ounce cola has 450 mg. One slice of processed cheese? 250 mg. A fast-food burger? Could be over 500 mg. That’s why dietitians tell you to avoid colas, processed meats, and anything with “phos” in the ingredient list.

Even dairy is tricky. Half a cup of milk has 125 mg of phosphorus, but it’s natural. A small portion is usually fine. But if you’re drinking milk with every meal, you’re overloading. Swap milk for unenriched rice milk or almond milk (check labels-some are fortified with phosphorus). Choose white bread over whole grain-white bread has 60 mg per slice, while whole grain has 150 mg.

Research in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (2022) showed that phosphorus additives increase absorption by 30-50% compared to natural sources. That’s why eating a grilled chicken breast is safer than eating chicken nuggets-even if the chicken itself is the same. The difference is in the processing.

There’s debate, though. The European Renal Association says restricting phosphorus below 1,200 mg/day doesn’t improve survival in non-dialysis patients. But most U.S. nephrologists still follow the 800-1,000 mg guideline because high phosphorus levels are linked to bone loss, itchy skin, and calcified blood vessels.

What to Eat: Real Food Swaps That Work

You don’t have to eat bland food. Here are simple, practical swaps that fit into real life:- Instead of orange juice, drink apple juice (unsweetened) or cranberry juice.

- Swap potatoes for white rice or pasta (rinse cooked rice to reduce potassium).

- Choose fresh chicken, turkey, or fish over deli meats or sausages.

- Use lemon juice or vinegar for flavor instead of salt.

- Replace cheese with small amounts of ricotta or cream cheese (lower in phosphorus than cheddar or processed slices).

- Snack on popcorn (no salt), rice cakes, or unsalted pretzels.

Protein intake matters too. Too little protein leads to muscle loss and weakness. Too much puts stress on your kidneys. The current KDOQI recommendation is 0.55-0.8 grams of high-quality protein per kilogram of body weight per day. That’s about 40-60 grams for most adults. Good sources include egg whites, lean fish (cod, halibut, tuna), and skinless chicken. A 3-ounce portion-about the size of a deck of cards-is enough.

Dr. Linda Fried at Columbia University found that proper dietary management can delay dialysis by 6-12 months in stage 4 CKD patients. That’s a year of staying off a machine, keeping your independence, and avoiding hospital visits.

Fluids, Supplements, and Daily Habits

If you’re producing less than 1 liter of urine a day, you’ll likely need to limit fluids to about 32 ounces (1 liter). That includes water, coffee, tea, soup, ice cream, and even gelatin. Sucking on ice chips can help with thirst without adding volume.Many people take supplements thinking they’re helping. But multivitamins often contain potassium or phosphorus. Only take supplements approved by your renal dietitian. Some CKD patients need special renal vitamins that exclude these minerals.

Apps like Kidney Kitchen (downloaded over 250,000 times) let you scan barcodes and see nutrient content in real time. They’re not perfect, but they help you make smarter choices when grocery shopping. The FDA approved the first medical food for CKD, Keto-1, in September 2023. It provides essential amino acids without phosphorus or potassium-useful for people struggling to get enough protein.

What About Diabetes and Kidney Disease?

Nearly half of new CKD cases come from diabetes. The problem? The foods doctors recommend for diabetes-whole grains, beans, nuts, fruits-are often high in potassium and phosphorus. A person with both conditions is caught between two diets that seem to contradict each other.DaVita’s 2023 analysis found that 68% of heart-healthy foods for diabetics are high in potassium or phosphorus. So you need a hybrid plan: choose lower-potassium fruits like berries, use white rice instead of brown, skip beans and lentils, and focus on lean proteins. Work with a renal dietitian who understands both conditions. You don’t have to give up good nutrition-you just need to adjust it.

When to See a Renal Dietitian

Most people try to manage this on their own. But it’s complex. What works for one person doesn’t work for another. Your potassium level might be fine one month and dangerously high the next. Your sodium needs change if you start dialysis. Your phosphorus tolerance shifts with age.Medicare now covers 3-6 sessions per year of renal nutrition counseling for stage 4 CKD patients. That’s because studies show it saves $12,000 per patient annually by delaying dialysis. A registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) specializing in kidney disease can create a meal plan that fits your taste, lifestyle, and lab results. They’ll teach you how to read labels, plan meals, and use food swaps that actually work.

It takes most people 3-6 months to get comfortable with the diet. The first few weeks are the hardest-everything tastes bland, and you miss your favorite foods. But with time, your taste buds adjust. You start noticing how much salt is hiding in your food. You learn to appreciate the natural flavor of grilled fish or roasted vegetables.

There’s no magic pill. But a well-managed renal diet is one of the most powerful tools you have to protect your health, avoid complications, and live longer with kidney disease.

Can I still eat fruits and vegetables on a renal diet?

Yes, but you need to choose wisely. Low-potassium options like apples, berries, cabbage, cauliflower, and green beans are safe in controlled portions. Avoid high-potassium fruits like bananas, oranges, kiwis, and dried fruit. Leaching vegetables-soaking and boiling them-can reduce potassium by up to 50%. Always check portion sizes and track your intake.

Is salt the only source of sodium in my diet?

No. About 75% of sodium comes from processed and restaurant foods, not table salt. Canned soups, frozen meals, deli meats, bread, and even breakfast cereals contain hidden sodium. Always read nutrition labels and look for “no salt added” or “low sodium” versions. Cooking at home with herbs instead of salt is the best way to control your intake.

Why are phosphorus additives worse than natural phosphorus?

Your body absorbs nearly 100% of inorganic phosphorus additives used in processed foods, compared to only 50-70% from natural sources like meat or dairy. Additives are found in colas, processed cheeses, deli meats, and baked goods. Even if the total phosphorus number looks similar on a label, the additive form is far more dangerous for your kidneys. Avoid anything with “phos” in the ingredients list.

Do I need to limit protein on a renal diet?

Yes, but not too much. Too much protein increases waste buildup in your blood. Too little can cause muscle loss and weakness. The current recommendation is 0.55-0.8 grams of high-quality protein per kilogram of body weight per day. Good sources include egg whites, skinless chicken, fish, and lean cuts of meat. A 3-ounce portion (size of a deck of cards) is usually enough per meal.

Can I drink soda on a renal diet?

Colas and dark sodas are high in phosphorus additives-about 450 mg per 12 oz can. Even diet versions contain these additives. Sparkling water, herbal tea, or lemon water are safer choices. If you must have soda, opt for clear sodas like ginger ale or lemon-lime, but still limit them. Water is always the best option.

How long does it take to adjust to a renal diet?

Most people need 3-6 months to get used to the changes. At first, food may taste bland without salt or sugar. But over time, your taste buds adapt. You start noticing flavors you didn’t before-like the sweetness of apples or the earthiness of roasted vegetables. Support from a renal dietitian and using herbs, spices, and citrus can make the transition easier.

Christina Widodo January 12, 2026

I never realized how much sodium was hiding in my breakfast cereal until I started reading labels. Now I make my own oatmeal with cinnamon and apples - tastes better anyway. My BP dropped 10 points in two months. No meds needed.

Also, leaching potatoes? Total game changer. I used to hate kidney-friendly diets until I learned this trick. Now I eat mashed potatoes weekly without guilt.

Prachi Chauhan January 12, 2026

so many people think kidney diet = boring food but its not true. its about smart swaps. like white rice over brown. lemon juice instead of salt. i cook for my dad with stage 4 ckd and he says the grilled cod with garlic and herbs tastes like luxury now. no more processed stuff. its not hard, just new.

Katherine Carlock January 13, 2026

thank you for this. i’ve been scared to even look at nutrition labels since my diagnosis. but this broke it down like i’m 5. i’m trying the rice milk swap tomorrow. and yes, i cried when i realized i could still eat blueberries. tiny wins, you know?

also, i made a chart of safe fruits and taped it to my fridge. it’s helping. we’re all just trying to survive this.

Sona Chandra January 13, 2026

why do doctors make this so complicated? just stop eating everything. that’s the answer. no more fruit, no more cheese, no more bread. why give us 100 rules when one rule works? eat nothing. live longer. simple. stop overthinking. your kidneys don’t care about your feelings.

Jennifer Phelps January 14, 2026

leaching veggies works but its such a pain. i tried it once and my potatoes still tasted like dirt. and why is phosphorus in everything? i just want a cheeseburger. why is life like this. also i read somewhere that plant phosphorus is fine but i forgot where. anyone remember?

also my mom says i should eat more eggs but i dont know if whites are ok anymore. help.

beth cordell January 14, 2026

OMG YES to the apple juice over orange juice swap!! 🍎🥤

and leaching potatoes?? I did it last week and it was like magic 🧙♀️

also i started using Mrs. Dash and now my food tastes like it’s on a cooking show 🌿✨

you guys are doing amazing. i’m rooting for all of us 💪❤️

Lauren Warner January 15, 2026

Let’s be real. Most of these ‘tips’ are for people who have time, money, and access to fresh produce. I work two jobs. I don’t have time to soak potatoes. I don’t have a car to get to the organic store. My ‘renal diet’ is whatever’s on sale at the corner store. So don’t lecture me about sodium labels. You’re not living my life.

Craig Wright January 16, 2026

The American approach to dietary management is overly complex and lacks discipline. In the UK, we follow evidence-based guidelines without the unnecessary emphasis on flavor swaps or emotional support. The goal is physiological stability, not taste satisfaction. One must prioritize function over preference. This article indulges in sentimentality at the expense of clinical rigor.

Lelia Battle January 18, 2026

I’ve been managing CKD for eight years now. The hardest part wasn’t the diet - it was the loneliness. No one talks about how isolating it feels to sit out at dinner parties because your food looks ‘boring.’

But I found a community online. We share recipes, vent, and celebrate small wins - like the first time you eat a grilled chicken breast without craving salt.

It’s not perfect. But it’s enough.

Rinky Tandon January 19, 2026

you people are wasting time with leaching and rice milk. the real problem is the pharmaceutical industry pushing fake nutrients. they want you dependent on renal vitamins and special foods. why not just eat real food? why are we letting corporations dictate our meals? you think your apple juice is safe? it’s processed too. everything is poisoned. you’re being manipulated.

Ben Kono January 20, 2026

phosphorus additives are the worst. i saw phos in my yogurt and i almost threw it out. why do they even put it in? i just want milk. why is everything so complicated. i miss pizza.

Cassie Widders January 21, 2026

Just wanted to say thanks. I’ve been reading this post three times. I’m not great with details but the part about sodium in bread? That was a lightbulb moment. I’ll start checking labels tomorrow. No drama. Just… trying.

Konika Choudhury January 22, 2026

indian food is the worst for ckd. dal chawal roti everything has potassium. my aunt made sambar and i cried. we need a south asian renal diet guide. no one talks about this. why is all this info only in english and american style? we need curry-friendly swaps.

Darryl Perry January 22, 2026

Article is 80% common sense. The rest is marketing. Dialysis patients need protein. Low protein diets are outdated. The real issue is compliance. Most people can’t follow this. So stop pretending it’s simple. It’s not. And no, you can’t ‘adjust’ your taste buds in 3 months. You just get used to being hungry.