Most people get vaccines without any issues. But when something does go wrong, the fear spreads fast. You hear about someone having a reaction, and suddenly, vaccines feel risky. The truth? Severe allergic reactions to vaccines are incredibly rare - so rare that you’re more likely to be struck by lightning than to have a life-threatening reaction after getting a shot. Still, it’s important to understand what actually happens, how it’s tracked, and what to do if you’re worried.

How Rare Are Allergic Reactions to Vaccines?

Let’s start with numbers that matter. Across all vaccines, anaphylaxis - the most serious type of allergic reaction - happens in about 1.3 cases per million doses. That’s less than one in a million. For the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, the rate was slightly higher: around 5 to 11 cases per million doses. That sounds scary until you realize that means over 99.999% of people who got those vaccines had no serious reaction at all.

Compare that to everyday risks: the chance of dying in a car crash in the U.S. is about 1 in 107 over a lifetime. The risk of a severe vaccine reaction? One in a million. You’re more likely to be injured by a vending machine than to have a true allergic reaction to a vaccine.

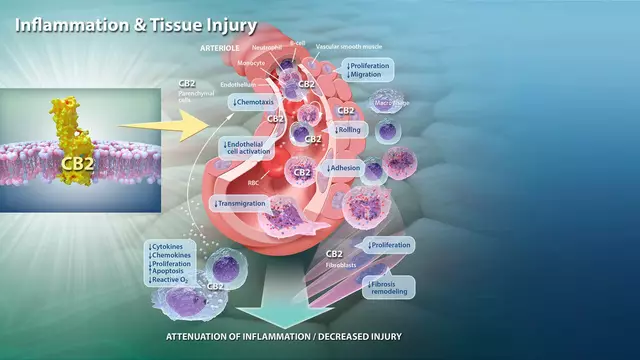

Most reactions that get reported aren’t even true allergies. Skin rashes, itching, or swelling at the injection site happen in 5% to 13% of people - but these are usually mild, go away on their own, and aren’t caused by the immune system overreacting like in anaphylaxis. True IgE-mediated allergies? Those are the ones that cause breathing trouble, swelling of the throat, or a sudden drop in blood pressure. They’re rare. And they almost always happen fast.

When Do Reactions Happen - And Why?

Timing is everything. About 86% of anaphylaxis cases start within 30 minutes of vaccination. More than 70% happen in the first 15 minutes. That’s why clinics ask you to wait after getting a shot. It’s not just tradition - it’s science. If something’s going to go wrong, it’s going to happen quickly.

The triggers? Most often, they’re not the virus or bacteria in the vaccine. They’re the other ingredients: polyethylene glycol (PEG) in mRNA vaccines, or proteins used to grow the vaccine, like yeast or chicken egg proteins. For years, people with egg allergies were told to avoid flu shots. That changed after studies showed over 4,300 egg-allergic people - including 656 with past anaphylaxis to eggs - got flu vaccines without serious issues. Today, no special precautions are needed for egg-allergic individuals.

Yeast allergies are even rarer. Only 15 possible cases were ever flagged in over 180,000 allergy reports to the U.S. safety system. And even then, it wasn’t clear if yeast was the real cause. Aluminum, used as an adjuvant in many vaccines, doesn’t cause anaphylaxis. It can cause lumps under the skin that last for months, but that’s a local reaction, not a systemic allergy.

Who’s Most Likely to Have a Reaction?

Women make up 81% of reported allergic reactions to vaccines. The average age? Around 40. That doesn’t mean women are more allergic - it likely reflects higher vaccination rates and more frequent reporting. People with a history of severe allergies - especially to medications, foods, or previous vaccines - are at slightly higher risk. But even then, the absolute risk remains tiny.

One important note: if you’ve had a confirmed anaphylaxis reaction to a vaccine before, you should see an allergist before getting another dose of the same vaccine. But that doesn’t mean you can’t get vaccinated. Many people with past reactions can safely receive future doses after testing and careful observation.

How Are Reactions Tracked and Managed?

The U.S. has one of the most advanced vaccine safety systems in the world: the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, or VAERS. It’s not perfect - it collects reports from anyone: doctors, patients, parents. That means some reports are inaccurate or unrelated. But it’s designed to catch patterns. If 100 people report the same reaction after getting a new vaccine, that’s a red flag. That’s how they spotted the slightly higher anaphylaxis rate with mRNA vaccines early on.

Doctors are required to report any suspected anaphylaxis to VAERS within 24 hours. Manufacturers must report serious events within 15 days. That’s not bureaucracy - it’s early warning. The system caught the link between the 1976 swine flu vaccine and Guillain-Barré syndrome. It flagged the rare blood clot cases with certain COVID vaccines. And it keeps working every day.

Every vaccination site must have epinephrine on hand. That’s the only medication that can stop anaphylaxis in its tracks. Staff are trained to use it. They also have blood pressure cuffs, timers, and emergency plans. If you feel dizzy, short of breath, or break out in hives after a shot, tell them immediately. They’re ready.

What Should You Do Before Getting Vaccinated?

If you’ve never had a reaction to any vaccine or medication, you don’t need to do anything special. Just show up. The benefits far outweigh the risks.

If you have a history of severe allergies - especially to any vaccine ingredient like PEG or polysorbate - talk to your doctor or allergist. You don’t need a skin test for most vaccines. But if you’ve had a confirmed anaphylaxis to a previous dose, an allergist can help determine if it’s safe to get another one, sometimes using graded dosing or pre-medication.

And if you’re egg-allergic? Go ahead and get the flu shot. No special waiting. No extra steps. No need to avoid it. The same goes for the MMR vaccine. Egg is used in making it, but the final product doesn’t contain enough to cause a reaction.

For the COVID-19 vaccines, if you’ve had anaphylaxis to PEG before, you should avoid mRNA vaccines. But there are alternatives, like Novavax, which doesn’t contain PEG. Your doctor can help you choose.

What Happens After a Reaction?

If you have a reaction, it’s not the end of your vaccination journey. Most people who survive anaphylaxis can still get vaccinated safely in the future - under medical supervision. Allergists can do tests to figure out what caused it. Sometimes it’s a specific ingredient. Sometimes it’s a combination. Sometimes, we don’t know.

And if you’re worried about future vaccines? The system is built to adapt. The CDC and FDA continuously update guidelines based on new data. In 2023, they refined advice for people with PEG allergies. In 2024, they updated recommendations for people with a history of mast cell disorders. These aren’t arbitrary changes. They’re based on real-world data from millions of doses.

There’s even research underway to predict who might react. Scientists are looking at mast cell markers in the blood that could signal risk before a shot. That’s still years away from being routine - but it’s coming.

Why This Matters

When people avoid vaccines because they’re scared of allergic reactions, it’s not just them who suffer. It’s their families. Their neighbors. Their communities. Measles outbreaks happen when vaccination rates drop. Polio can return. Whooping cough kills babies.

The system we have - VAERS, CDC monitoring, allergist evaluations, epinephrine on every corner - exists because we take safety seriously. Not because reactions are common. But because even one preventable death is too many.

So if you’re hesitant because of a story you heard, ask yourself: does the fear match the data? Anaphylaxis after vaccines is rarer than being hit by lightning. But the protection vaccines offer? It’s life-saving.

Don’t let rare risks stop you from getting the protection you need. Understand the facts. Talk to your doctor. And get vaccinated.

sean whitfield December 5, 2025

So let me get this straight - we're told to trust a system that can't even tell if a vaccine caused a reaction or if someone just ate peanuts 2 hours before?

VAERS is a joke. Anyone can report anything.

They call it 'safety' but it's just PR with a spreadsheet.

Mark Curry December 7, 2025

I get scared too sometimes. But then I remember my cousin's kid got sick with measles because they didn't vaccinate.

It's not about fear. It's about protecting the ones who can't fight it themselves.

❤️

aditya dixit December 8, 2025

The data is clear: severe reactions are statistically negligible.

What matters more is the collective responsibility we carry when we choose to vaccinate.

Not every risk is worth avoiding if the benefit saves lives.

Peaceful coexistence with science is not weakness.

Ada Maklagina December 9, 2025

I had a rash after my second shot. Felt like a zombie for two days.

Still got the booster. Worth it.

Katie Allan December 11, 2025

It's not about ignoring fear. It's about not letting fear make decisions for you.

People die from preventable diseases every day.

Vaccines are one of the few tools we have that actually work.

Don't let noise drown out the science.

Deborah Jacobs December 13, 2025

I used to be terrified of needles. Then I watched my grandma struggle to breathe during her last pneumonia attack.

She never got the shot.

Now I get every one.

My skin breaks out? Big deal.

My lungs working? Priceless.

And yeah, I cried during my first shot.

But I also laughed when the nurse handed me a lollipop.

Life's weird like that.

James Moore December 14, 2025

Let me be perfectly clear: this whole system is a corporate-government psy-op designed to normalize chemical injection into the human body under the guise of 'health'!

Who benefits? Big Pharma, of course!

They make billions off fear!

And you? You're the lab rat!

They're testing PEG, aluminum, polysorbate-names you can't pronounce-on your kids!

And you just sit there, nodding like a puppet, because the media told you to!

Wake up!

They don't want you healthy-they want you compliant!

And don't even get me started on the CDC's 'conflicts of interest'!

It's all connected!

Someone's making money off your fear-and your silence!

Kylee Gregory December 16, 2025

I think the most important thing here isn't the numbers-it's the trust.

We trust doctors, scientists, nurses-they're the ones standing there with epinephrine in hand, waiting to help if something goes wrong.

That's not a system designed to deceive.

That's a system designed to care.

Lucy Kavanagh December 16, 2025

I read somewhere that PEG is in toothpaste and makeup too... so why is it suddenly dangerous in a vaccine?

Maybe they're just trying to make us scared so we'll buy more 'safe' products?

And why do they always say 'rare' but never say 'never'?

That's the thing... they never say 'never'.

And that's scary.