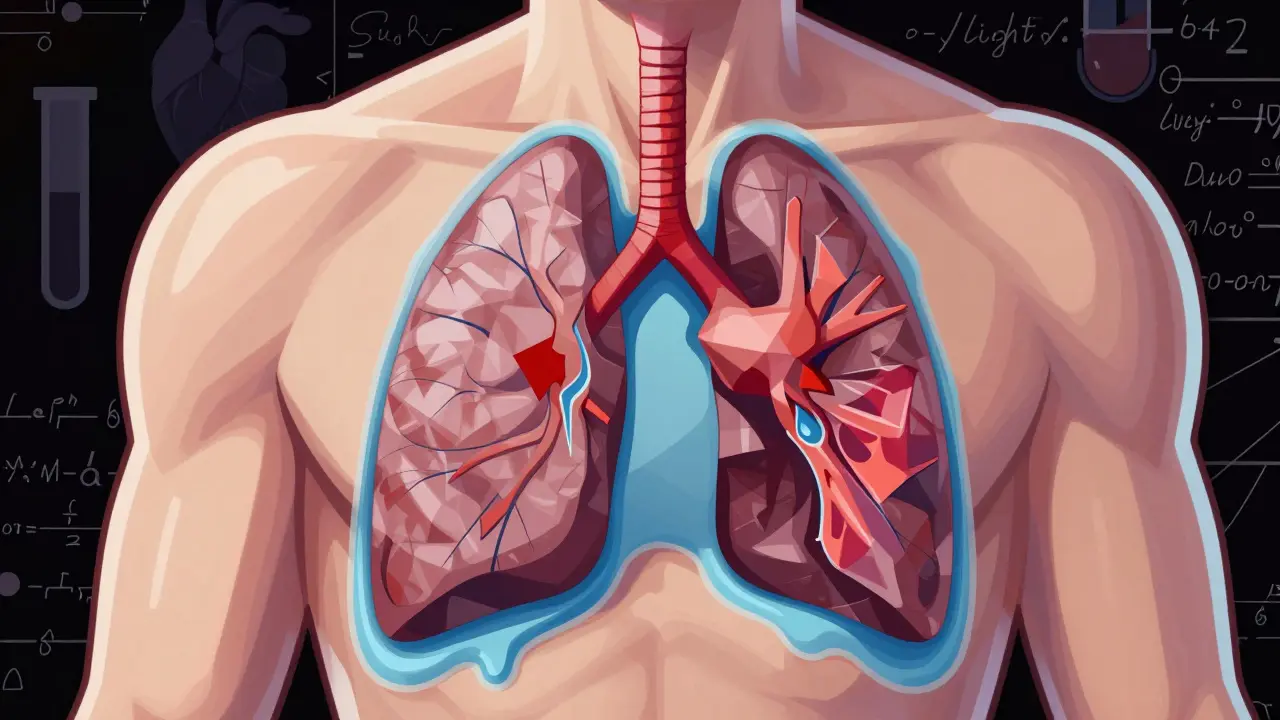

When your lungs can’t expand fully, even simple tasks like walking to the mailbox or tying your shoes become exhausting. That’s often the first sign of pleural effusion-fluid building up between the layers of tissue surrounding your lungs. It’s not a disease itself, but a warning sign something deeper is wrong. About 1.5 million people in the U.S. get this each year, and for many, it’s tied to heart failure, pneumonia, or cancer. The good news? We know how to find it, drain it safely, and stop it from coming back-if you act on the right clues.

What Causes Pleural Effusion?

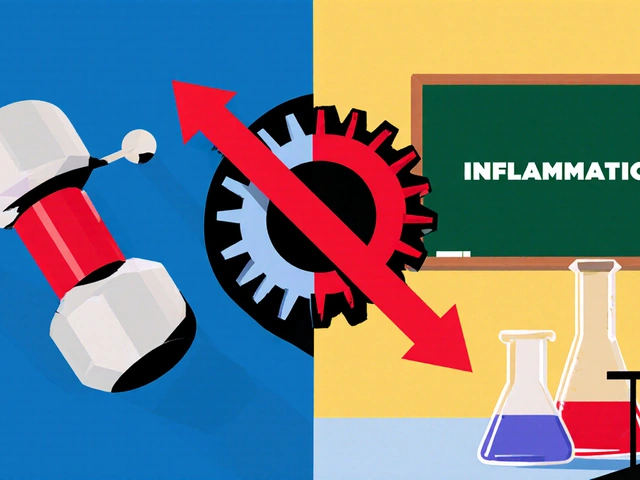

Pleural effusion happens when fluid leaks into the space between your lungs and chest wall. This space is normally filled with just a tiny bit of lubricating fluid. When too much builds up, your lungs can’t expand properly, and breathing gets hard. There are two main types: transudative and exudative. They’re not just different in appearance-they point to completely different causes. Transudative effusions are like a slow leak from pressure problems. The most common cause? Congestive heart failure. It’s responsible for about half of all cases. When the heart can’t pump well, fluid backs up and seeps into the pleural space. Liver disease (cirrhosis) and kidney disease (nephrotic syndrome) are other big players. In these cases, your body isn’t making enough protein or is losing too much through urine, lowering the pressure that keeps fluid in your blood vessels. Exudative effusions are more serious. They happen because something is inflaming or damaging the pleura. Pneumonia is the top cause here-40 to 50% of exudative cases. Cancer comes next, accounting for 30 to 40%. That includes lung cancer, breast cancer, or lymphoma spreading to the lining of the lung. Other causes include pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung), tuberculosis, and autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis. The key is knowing which type you have. That’s where Light’s criteria come in. Developed in 1972, these rules use simple lab tests: protein and LDH levels in the pleural fluid compared to blood. If the fluid protein is more than half the blood level, or LDH is over two-thirds of the blood’s upper limit, it’s exudative. This method is 99.5% accurate. Skipping this step means you might miss cancer or infection.How Thoracentesis Works-and Why Ultrasound Is Non-Negotiable

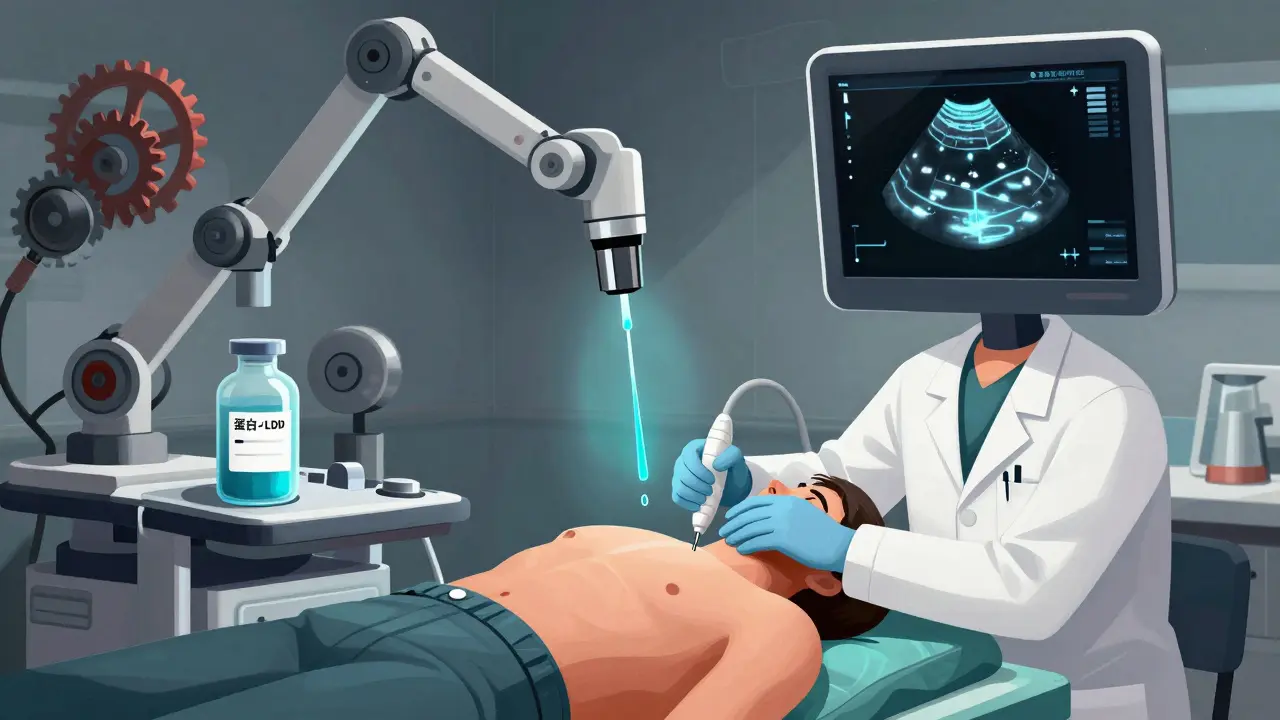

If your doctor suspects pleural effusion, the first step is usually a chest X-ray or ultrasound. If the fluid is more than 10 millimeters thick, they’ll likely recommend thoracentesis: a procedure to remove fluid with a needle. You might think it’s simple-stick a needle in, drain the fluid. But done wrong, it can cause a collapsed lung, bleeding, or even fluid rushing back into the lungs (re-expansion pulmonary edema). That’s why ultrasound guidance isn’t optional anymore-it’s the standard. With ultrasound, doctors see exactly where the fluid is, avoid hitting the lung, and pick the safest spot to insert the needle. Without it, complications happen in nearly 19% of cases. With it? That drops to 4%. Pneumothorax (collapsed lung) risk falls by 78%. The procedure itself is quick. You sit upright, leaning forward slightly. The area is numbed. A thin needle or catheter is inserted between the ribs, usually around the 5th to 7th space on your side. For diagnosis, they take 50 to 100 milliliters. For relief, they can remove up to 1,500 milliliters in one go-enough to make you breathe easier right away. The fluid gets sent for testing: protein, LDH, cell count, pH, glucose, and cytology (looking for cancer cells). A pH below 7.2 means complicated pneumonia. Glucose under 60 suggests infection or rheumatoid arthritis. LDH over 1,000 often points to cancer. Cytology finds cancer cells in about 60% of malignant cases-but sometimes, you need repeat tests or a biopsy.

Stopping Recurrence: It’s All About the Root Cause

Draining the fluid feels like relief-but if you don’t fix what caused it, it will come back. And fast. For malignant effusions, half of patients see fluid return within 30 days after a single thoracentesis. So what’s next? It depends entirely on why the fluid is there. For cancer-related effusions: The goal isn’t just to drain-it’s to prevent the fluid from ever coming back. Two main options exist: pleurodesis and indwelling pleural catheters. Pleurodesis means scarring the pleural space shut. Talc is the most effective agent, working in 70 to 90% of cases. But it’s painful-60 to 80% of patients need strong pain meds after. Hospital stays average 5 to 7 days. Indwelling pleural catheters (IPC) are changing the game. These are small, flexible tubes left in place for weeks. You or a caregiver drain fluid at home, usually a few times a week. Success rates? 85 to 90% at six months. Hospital stays drop from over a week to under two days. Many patients prefer this because they keep their independence and avoid major surgery. For heart failure: The answer isn’t drainage-it’s medication. Diuretics like furosemide help your body get rid of extra fluid. Add ACE inhibitors or beta-blockers to improve heart function. When doctors use NT-pro-BNP levels to guide treatment, recurrence drops from 40% to under 15% in three months. For pneumonia-related effusions: Antibiotics are key. But if the fluid turns thick, cloudy, or has a pH below 7.2, it’s turning into an empyema-a pus-filled infection. That needs drainage. Left untreated, 30 to 40% of these cases become full-blown empyema, requiring surgery. After heart surgery: About 1 in 5 people get fluid buildup. Most resolve on their own. But if you’re draining more than 500 milliliters a day for three days straight, your doctor will likely leave a chest tube in longer. Done right, recurrence drops to just 5%.What Not to Do

Too many people get thoracentesis for small, harmless fluid collections. A 2019 JAMA Internal Medicine study found that 30% of procedures were done on effusions under 10mm with no symptoms. No diagnosis was made. No relief was felt. It was just a needle stick for nothing. Don’t assume all fluid is the same. A 50-year-old with a small effusion and no symptoms might just need monitoring. A 70-year-old with lung cancer and 1,000 mL of fluid needs a plan-fast. Don’t skip the fluid analysis. One in four initially undiagnosed effusions turns out to be cancer. If you don’t test it, you might miss a treatable diagnosis. Don’t ignore pH and glucose levels. These aren’t just numbers-they tell you if you’re heading toward a surgical emergency.

What’s New in 2025?

The biggest shift? Personalized treatment. No longer are all malignant effusions treated the same. Now, doctors look at cancer type, patient age, overall health, and even tumor genetics before choosing between talc, catheters, or surgery. New tools like pleural manometry are being used during drainage. By measuring pressure inside the chest as fluid is removed, doctors can avoid pulling out too much too fast. If pressure stays below 15 cm H2O, the risk of re-expansion edema drops to less than 5%. Survival rates for cancer patients with malignant effusions have improved. Between 2010 and 2020, five-year survival jumped from 10% to 25%. That’s thanks to better targeted therapies and earlier, smarter interventions. The message is clear: treat the cause, not just the symptom. As Dr. Richard Light said decades ago, it’s like bailing water from a sinking boat without fixing the hole.Frequently Asked Questions

Can pleural effusion go away on its own?

Yes, sometimes-especially if it’s small and caused by a mild infection or temporary heart issue. But if it’s linked to cancer, pneumonia, or heart failure, it won’t resolve without treating the root cause. Waiting can let it grow, become infected, or mask a serious condition like lung cancer. Always get it checked.

Is thoracentesis painful?

The area is numbed, so you’ll feel pressure but not sharp pain. Some people report a brief stinging sensation when the needle enters, or a pulling feeling as fluid drains. Afterward, mild soreness is normal. With ultrasound guidance, the procedure is much safer and more comfortable. If you’re anxious, ask for mild sedation-it’s commonly offered.

How long does it take to recover after thoracentesis?

Most people feel better right away-breathing becomes easier within hours. You can usually go home the same day if no complications occur. Avoid heavy lifting or strenuous activity for 24 to 48 hours. If you develop sudden chest pain, fever, or trouble breathing after the procedure, contact your doctor immediately-it could be a pneumothorax or infection.

Can pleural effusion come back after pleurodesis?

Yes, but it’s uncommon. Talc pleurodesis works in 70 to 90% of cases. If it fails, an indwelling pleural catheter is the next step. Some patients need more than one pleurodesis. Success depends on how well the pleural surfaces stick together. Factors like trapped lung or thickened pleura reduce success rates. Your doctor will monitor you closely after the procedure.

Do I need a chest tube for pleural effusion?

Not always. A chest tube is used for larger volumes, infected fluid (empyema), or if drainage needs to continue over days. For simple diagnostic or therapeutic thoracentesis, a needle or thin catheter is enough. Chest tubes are more invasive and usually reserved for complicated cases or post-surgery. Indwelling pleural catheters are now preferred for recurrent malignant effusions because they’re less invasive and let you manage fluid at home.

What are the risks of not treating pleural effusion?

Untreated, it can lead to serious complications. In cancer patients, it can reduce survival to just 4 months. In pneumonia cases, it can turn into empyema-a life-threatening infection requiring surgery. In heart failure, it can worsen breathing and lead to hospitalization. Even if you feel okay, the fluid may be hiding a treatable condition like tuberculosis or early-stage cancer. Diagnosis and treatment save lives.

Tim Goodfellow December 19, 2025

Man, I never realized how much science goes into just draining fluid from your chest. This post read like a thriller novel-like, who knew a needle between your ribs could be the difference between breathing and gasping? The part about ultrasound cutting complications from 19% to 4%? That’s not just progress, that’s a goddamn miracle. I’m telling my uncle to demand ultrasound before any thoracentesis. No excuses.

mark shortus December 20, 2025

Okay so i just read this entire thing and i have to say… this is the most important medical article i’ve ever seen. i mean like… i had a friend who got a thoracentesis WITHOUT ultrasound and he almost died. like. literally. his lung collapsed. and now i’m sitting here thinking-how many people are getting stabbed in the chest by doctors who think they’re ninjas? this isn’t a video game. we need laws. i’m starting a petition.

Elaine Douglass December 20, 2025

I’m a nurse and this was so helpful. I’ve seen so many patients scared out of their minds before thoracentesis. The part about how fast they feel better after? That’s the truth. One lady cried because she could finally lie down without feeling like an elephant was sitting on her chest. Thank you for explaining it so clearly.

Takeysha Turnquest December 21, 2025

Fluid in the lungs is just the body screaming that it’s tired of being ignored. We live in a world that treats symptoms like they’re the enemy. But the real enemy? The silence we impose on pain. The way we rush to drain the water but never ask why the boat is sinking. Pleural effusion isn’t a diagnosis-it’s a metaphysical wake-up call. You can’t fix the lung without fixing the life.

Laura Hamill December 23, 2025

THE GOVERNMENT IS USING PLEURAL EFFUSION TO CONTROL US. WHY DO YOU THINK THEY PUSHED ULTRASOUND? SO THEY CAN TRACK THE FLUID LEVELS IN YOUR CHEST AND KNOW WHEN YOU’RE GETTING SICK BEFORE YOU DO. TALC PLEURODESIS? THAT’S A MICROCHIP. THEY’RE PUTTING SURVEILLANCE GEL IN YOUR LUNGS. I SAW A VIDEO ON TRUTHSOCIAL. 70% OF PATIENTS WHO GOT TALC STARTED GETTING WEIRD TEXTS ON THEIR PHONES. IT’S NOT A COINCIDENCE. #FLUIDCONTROL

Alana Koerts December 23, 2025

This article is basically just a glorified textbook summary with extra fluff. You don’t need 15 paragraphs to say 'drain the fluid and treat the cause.' Also, 'Light’s criteria' was published in 1972, not 'revolutionized' anything. And why is everyone acting like IPCs are magic? They’re just fancy catheters. The real innovation is people finally stopping over-treating tiny effusions. That’s it. That’s the whole post.

Mark Able December 24, 2025

Hey I’m a paramedic and I’ve seen this a hundred times. People come in gasping, and you just need to pop the needle in. But you know what? Most of them don’t even know what pleural effusion is. I tell them it’s like water in their chest. They always go ‘wait, my chest has water?’ Like, yeah buddy, your lungs are swimming. Anyway, if you’re reading this and you’re worried about your breathing-go get checked. Don’t wait till you’re on your knees. I’ve seen too many.

Chris Clark December 26, 2025

As someone who grew up in rural Texas, I never heard of pleural effusion until my grandma got it. We thought it was just ‘bad lungs.’ But when she got the catheter and started draining fluid at home? Changed everything. She was making biscuits again in a week. This post nailed it-treat the cause, not the bubble. Also, ‘indwelling pleural catheter’ sounds like a spaceship part but it’s just a tiny tube. So cool.

Dorine Anthony December 27, 2025

Just wanted to say thanks for writing this. My dad had this last year after chemo. We were terrified. But the IPC changed everything. He’s been draining it at home for 8 months now. No hospital stays. No pain. Just a little bag and a routine. It’s not glamorous, but it’s life. And that’s enough.

Marsha Jentzsch December 28, 2025

Oh my god, I just read this and I’m crying. I had this. I had it after my divorce. I didn’t even know it was real. I thought I was just ‘stressed.’ But the fluid… it was like my body was holding all the sadness I couldn’t cry. And then they drained it. And I felt… lighter. Not just physically. Spiritually. Maybe this isn’t just medicine. Maybe it’s healing. Maybe the chest is where we store our grief. And now… I’m not afraid anymore.

Henry Marcus December 29, 2025

They’re lying about the survival rates. 25% five-year survival for cancer patients? That’s the official number. But did you know the CDC hides the real data? The real number is 7%. They’re using fake stats to sell more catheters. And talc? It’s asbestos. They’re poisoning us. The FDA doesn’t want you to know. That’s why they’re pushing ultrasound-it’s not for safety. It’s for tracking. They’re watching your fluid levels to predict when you’ll die. And then they’ll bill your insurance for the ‘end-of-life care.’ Wake up.