When you’re over 65, the same pill that worked perfectly at 45 might make you dizzy, confused, or even sick. That’s not because the medicine changed - it’s because your body did. As we age, our organs don’t work the same way. Your liver processes drugs slower. Your kidneys filter them out less efficiently. Your body holds onto more fat and loses muscle. All of this changes how medications behave inside you. Yet, most prescriptions are still written using standard adult doses - doses designed for people in their 20s and 30s. This mismatch is why medication dosage adjustments for aging bodies and organs aren’t optional. They’re essential.

Why Older Bodies Handle Medicines Differently

Your body changes after 65 in ways most people don’t realize. Take your kidneys. After age 30, your kidney function drops by about 8 mL per minute every decade. By 75, many people have lost nearly half their kidney filtering power. That’s critical because over 40% of all prescription drugs are cleared through the kidneys. If your kidneys can’t flush out a drug like gabapentin or metformin, it builds up. Too much builds up, and you get side effects - falls, confusion, nausea, even kidney damage. Your liver isn’t working at full speed either. Hepatic clearance drops by 30-50% for many common drugs. That means medications like benzodiazepines (sleep aids), statins (cholesterol drugs), and even some painkillers stick around longer. They don’t just last longer - they become more powerful. A 5 mg dose of a sleeping pill might be enough for a 70-year-old, while a 30-year-old needs 10 mg. Give the same dose to both, and the older person is at risk of overdose. Then there’s body composition. Older adults tend to have more body fat and less muscle. Fat-soluble drugs like diazepam or amitriptyline get stored in fat tissue and release slowly, leading to prolonged effects. Water-soluble drugs like lithium or digoxin, on the other hand, become more concentrated because there’s less water in the body to dilute them. Even small changes in weight or hydration can throw off the balance.The Four Phases of Drug Changes in Aging

Doctors and pharmacists look at four key phases when adjusting doses for older adults:- Absorption: Stomach acid drops, blood flow to the gut slows. This means some pills don’t dissolve or get absorbed as quickly. It’s why some medications work slower or less predictably in seniors.

- Distribution: Less muscle, more fat, less total body water - this changes where drugs go in your body. A drug meant to stay in your bloodstream might end up trapped in fat tissue, or become too concentrated in your blood.

- Metabolism: Your liver’s ability to break down drugs declines. Drugs processed by the liver - like antidepressants, blood thinners, and anticonvulsants - can build up to dangerous levels.

- Excretion: Kidneys filter drugs out. When kidney function drops below 50 mL/min (a common threshold), many drugs need dose cuts of 25-50%.

These aren’t guesses. They’re measurable, documented changes backed by decades of clinical research. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria® (updated in 2023) lists 30 drug classes that are risky for seniors - from sleeping pills to NSAIDs like ibuprofen, which can cause internal bleeding in older adults at a rate 300% higher than in younger people.

How Doses Are Actually Adjusted

There’s no one-size-fits-all formula, but there are proven methods doctors use. For drugs cleared by the kidneys, the Cockcroft-Gault equation is the gold standard. It uses your age, weight, and blood creatinine level to estimate how well your kidneys are working. If your creatinine clearance (CrCl) falls below 50 mL/min, most drugs need a dose reduction. For example:- Gabapentin: Standard dose is 300 mg three times a day. For seniors with CrCl under 50, it’s cut to 100-150 mg once or twice daily.

- Metformin: Stopped entirely if eGFR drops below 30. Reduced to 500 mg daily if eGFR is between 30-45.

- Warfarin: Often started at 1-2 mg daily instead of 5 mg, with slower titration and more frequent blood tests.

For liver-metabolized drugs, the Child-Pugh score helps. If your liver function is moderately impaired (score 7-9), doses are cut by 50%. If severely impaired (score 10-15), the drug may be avoided altogether.

For drugs with a narrow safety window - like digoxin, lithium, or phenytoin - therapeutic drug monitoring is used. Blood levels are checked regularly. In seniors, the target range for digoxin is 0.5-0.9 ng/mL, not the 0.8-2.0 ng/mL used in younger adults. Too high? Risk of fatal heart rhythm problems. Too low? The drug doesn’t work.

High-Risk Medications for Seniors

Some drugs are simply too dangerous for older adults, even at low doses. The 2023 Beers Criteria® highlights these as red flags:- Benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam, diazepam): Increase fall risk by 50%. Linked to memory loss and dementia with long-term use.

- NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen): Cause stomach bleeding, kidney damage, and heart failure in up to 20% of seniors taking them daily.

- Anticholinergics (e.g., diphenhydramine, oxybutynin): Double dementia risk with just 90 days of use. Found in many OTC sleep aids and allergy pills.

- First-generation antihistamines: Cause drowsiness, confusion, urinary retention - all dangerous for seniors.

- Long-acting sulfonylureas (e.g., glyburide): Cause dangerous low blood sugar that’s hard to reverse.

Many of these are still prescribed - often because doctors don’t know the alternatives or assume the patient “needs” them. But the evidence is clear: these drugs cause more harm than good in older adults. Safer options exist. For sleep, melatonin or cognitive behavioral therapy. For pain, acetaminophen (with caution) or physical therapy. For overactive bladder, mirabegron is safer than oxybutynin.

The Real-World Problem: Polypharmacy

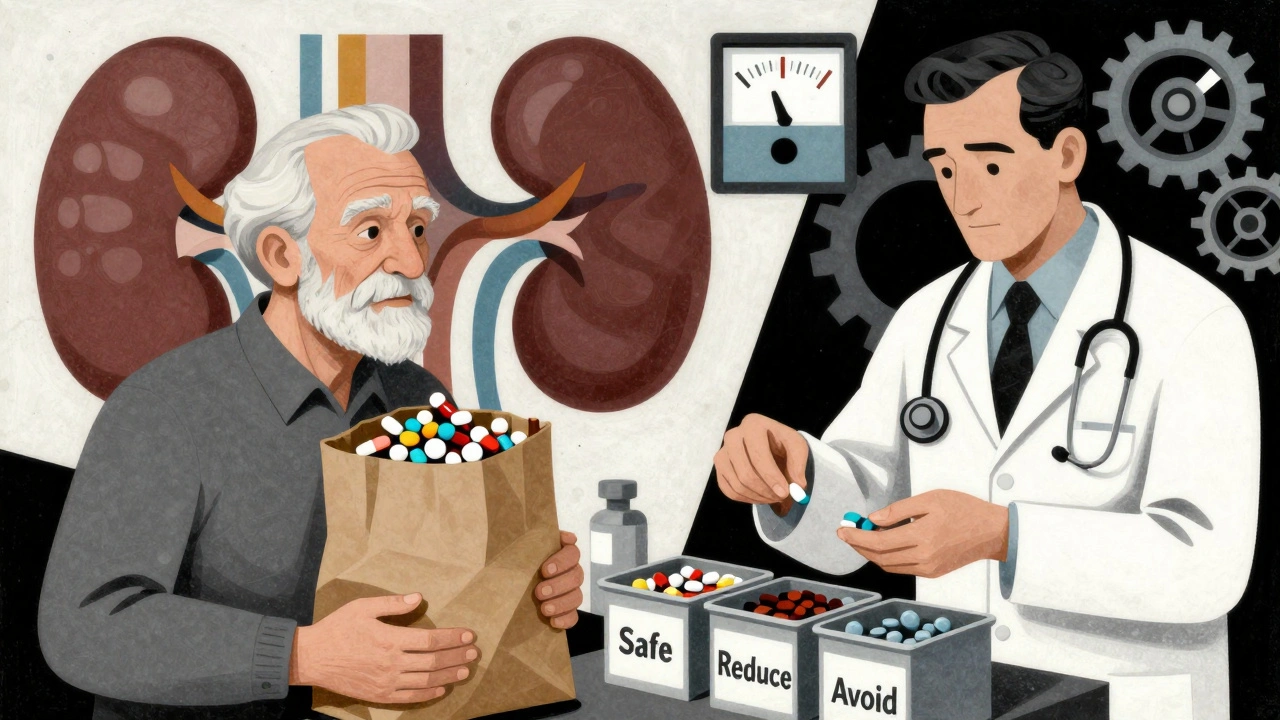

More than half of adults over 65 take five or more prescription drugs. That’s called polypharmacy. It’s not just about one bad pill - it’s about how they interact. A blood thinner, a diuretic, an antidepressant, a statin, and a painkiller - all taken together - can create a perfect storm. One drug might raise the level of another. Another might make your kidneys work harder. The result? Side effects pile up. Confusion. Falls. Hospital stays.That’s why the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) exists. It’s a 10-point checklist doctors use to rate each drug for appropriateness - indication, effectiveness, dose, duration, interactions, and more. A score above 18 means the regimen is inappropriate and needs urgent review.

One real-world fix? The “brown bag review.” Patients bring all their pills - prescriptions, supplements, OTC meds - to their doctor. It’s simple. It’s powerful. In one study, this practice caught 70% of dangerous interactions that weren’t in the electronic record.

Who Should Be Doing This Work?

Primary care doctors are stretched thin. A typical visit lasts 15-20 minutes. Reviewing 10 medications takes 35 minutes. That’s why pharmacists are becoming the backbone of safe prescribing for seniors.Pharmacists specializing in geriatrics can review every medication, check kidney and liver function, spot interactions, and suggest safer alternatives. A 2022 study found that pharmacist-led medication reviews reduced errors by 67%. In programs like the University of North Carolina’s Pharm400, weekly blister packs and monthly check-ins cut hospitalizations by 22%.

Electronic alerts in medical records help too. If a doctor prescribes a drug that’s risky for someone with low kidney function, the system can pop up a warning. One study showed this reduced dosing errors by 53%.

What Seniors and Families Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. Here’s what actually works:- Ask: “Is this still necessary?” Every six months, ask your doctor if each medication is still needed. Many are prescribed for short-term use but kept for years.

- Know your kidney number. Ask for your eGFR or creatinine clearance. If you don’t know it, you can’t know if your doses are right.

- Use one pharmacy. That way, all your meds are in one system. The pharmacist can spot interactions you won’t see.

- Bring your brown bag. Every visit. Every pill. No exceptions.

- Watch for new symptoms. Dizziness, confusion, fatigue, falls - these aren’t just “getting old.” They could be drug side effects.

Family caregivers play a huge role. A 2019 study found that when family members help manage meds, adherence improves by 37%. That’s not just about remembering pills - it’s about noticing when something feels off.

The Future: Personalized Dosing

The future isn’t about age. It’s about function.Researchers are moving beyond “65+” to measure actual health. Gait speed. Balance tests. Cognitive screens. The Timed Up and Go test - where you stand up, walk 3 meters, turn, walk back, and sit down - is now used to guide dosing. If it takes longer than 12 seconds, you’re frail. That means even more cautious dosing.

AI tools like MedAware are starting to predict risky dosing before it happens. In a 2023 Johns Hopkins pilot, the algorithm reduced errors by 47%. Soon, your doctor might get a real-time alert: “Patient has CrCl of 42. Gabapentin dose exceeds safe limit.”

By 2030, experts predict that 70% of high-risk medications for seniors will be dosed based on individual physiology - not just age. That’s the goal. Not just safer doses. Better outcomes. Fewer hospital stays. More independence.

Right now, the system is still catching up. But change is happening. And it starts with asking the right questions - and refusing to accept that “old age” means taking more pills just because that’s what’s on the label.

Why can’t seniors just take the same dose as younger adults?

Because aging changes how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and removes drugs. Kidneys and liver slow down, body fat increases, and muscle mass declines. These changes mean drugs stay in the body longer and at higher concentrations, increasing the risk of side effects. A standard adult dose can become toxic in an older person.

What is the Beers Criteria® and why does it matter?

The Beers Criteria® is a list of medications that are potentially inappropriate for older adults because they carry more risks than benefits. Updated every two years by the American Geriatrics Society, it identifies drugs like benzodiazepines, NSAIDs, and anticholinergics that can cause falls, confusion, kidney damage, or dementia. It’s a guide for doctors and pharmacists to avoid harmful prescriptions.

How do I know if my medication dose is too high?

Watch for new symptoms after starting or changing a dose: dizziness, confusion, memory lapses, unsteadiness, nausea, or extreme fatigue. If you’ve had a fall or been hospitalized after a medication change, ask your doctor to review all your drugs. Your kidney function (eGFR) and liver tests should also be checked regularly.

Can I stop a medication on my own if I think it’s causing problems?

Never stop a medication suddenly without talking to your doctor. Some drugs, like blood pressure pills or antidepressants, can cause dangerous withdrawal effects. But you absolutely should ask your doctor if a medication is still necessary - especially if you’re experiencing side effects. Many seniors can safely reduce or stop one or more drugs under medical supervision.

Do pharmacists really help with senior medication safety?

Yes - and studies prove it. Pharmacists who specialize in geriatrics can spot dangerous interactions, recommend safer alternatives, and adjust doses based on kidney and liver function. One study found pharmacist-led reviews reduced medication errors by 67%. Many hospitals and clinics now have geriatric pharmacists on staff specifically for this reason.

What’s the best way to keep track of all my medications?

Use the “brown bag review” - bring every pill, supplement, and OTC medicine to every doctor visit. Also, keep a written or digital list updated with the name, dose, reason, and time of day for each medication. Use a pill organizer with alarms if needed. And always use one pharmacy so all your meds are in one system.

Next Steps for Seniors and Caregivers

If you or a loved one is taking multiple medications, here’s what to do now:- Request your latest eGFR and creatinine clearance numbers from your doctor.

- Bring all medications - including vitamins and OTCs - to your next appointment.

- Ask: “Which of these are still necessary? Are any of them on the Beers Criteria® list?”

- Ask if a pharmacist can review your regimen.

- Watch for new symptoms after any dose change - and report them immediately.

Medication safety in older adults isn’t about cutting pills. It’s about matching the medicine to the person - not the age on the ID card. With the right approach, seniors can stay healthy, independent, and safe - without unnecessary drugs holding them back.

Ali Bradshaw December 5, 2025

Man, I wish my dad’s doctor had this info five years ago. He was on gabapentin for years until he started falling every other week. Turned out his kidneys were at 40% and the dose was still 300mg three times a day. Once they cut it down? He stopped stumbling around like a drunk toddler. Simple fix, but nobody asked.

Annie Grajewski December 6, 2025

so like… if your liver is ‘slowing down’ does that mean your meds are just vibin’ in your body like a lazy cat in a sunbeam? 😂 also why do doctors still write scripts like we’re all 25? i swear half the time they just copy-paste.

luke newton December 7, 2025

Of course this is true. But let’s be honest-this isn’t about science. It’s about the pharmaceutical industry’s refusal to acknowledge that aging isn’t a disease to be medicated. They profit from polypharmacy. They fund the studies that make you think you need five pills. And then they sell you the ‘safe’ alternatives… for $200 a month. Wake up.

Beers Criteria? That’s just a Band-Aid. The real problem is a medical system built on volume, not value. If you’re over 65 and still on statins? You’ve been sold a lie. Your cholesterol isn’t the enemy. The profit margin on Lipitor is.

Lynette Myles December 8, 2025

They’re hiding this from you. The CDC knows. The FDA knows. But if seniors stop taking these drugs, the nursing home industry collapses. They need you weak. They need you confused. They need you dependent.

Laura Saye December 8, 2025

This is so important. I’ve seen my mom go from 12 meds to 4 after a pharmacist review. She started sleeping through the night, stopped hallucinating at 3 a.m., and actually remembered my birthday. It wasn’t magic-it was just someone taking the time to listen. Thank you for putting this out there.

Juliet Morgan December 9, 2025

my grandma’s doctor gave her benzos for ‘anxiety’ and she didn’t even know she was on them for 3 years. she thought it was just ‘getting older.’ i found the bottle in her nightstand. she cried when i told her it wasn’t normal. please share this with your elders.

aditya dixit December 11, 2025

There’s a deeper truth here: medicine treats age as a number, but the body doesn’t care about calendars. It cares about function. A 70-year-old who hikes daily and lifts weights may metabolize drugs better than a 55-year-old with diabetes and obesity. We need to stop prescribing by birth year and start prescribing by biology. The science is already here. What’s missing is the will to change.

Mark Ziegenbein December 11, 2025

Look I’ve been in this game for 25 years and I’ve seen it all and let me tell you the system is rigged and the pharmaceutical reps are walking into every clinic in America with free lunches and branded pens and doctors are just signing the scripts because they’re tired and overworked and honestly it’s not their fault it’s the entire infrastructure that’s broken and we need to tear it down and rebuild it from the ground up with patient-centered care and not profit-driven nonsense and I’m not even mad I’m just disappointed because we could be doing so much better and we’re not and it’s heartbreaking

Norene Fulwiler December 13, 2025

In my country we don’t have this problem because our elders take herbal teas and walk every morning. But I’ve seen American seniors drowning in pills. It’s not medicine-it’s cultural surrender. You’re told to fix everything with a pill. But the body isn’t a machine. It’s a living thing that needs movement, silence, and time.

Jimmy Jude December 14, 2025

They’re not just prescribing wrong doses-they’re prescribing wrong lives. You’re not supposed to be old. You’re supposed to be fixed. But you can’t fix death. And they know it. That’s why they keep writing scripts. Because if they stop, they have to face the truth: we’re not meant to live 90 years on 12 drugs. We’re meant to live 70, healthy, and free.

an mo December 15, 2025

Let’s be clear: the Beers Criteria is a politically correct facade. The real issue is demographic collapse. With fewer working-age taxpayers, the system incentivizes institutionalization. Elderly polypharmacy isn’t medical-it’s economic engineering. The data is manipulated. The studies are funded by the same labs that patent the drugs. You’re being used as a revenue stream. And if you don’t believe me, check the SEC filings of the top 5 pharma companies. They don’t care if you live. They care if you buy.