When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. That’s not luck. It’s the result of strict bioequivalence studies required by the FDA. These studies are the backbone of the entire generic drug system in the U.S. Without them, there’d be no guarantee that a $5 generic tablet does the same job as its $50 brand-name cousin.

What Bioequivalence Actually Means

Bioequivalence isn’t about looking the same or tasting the same. It’s about how your body absorbs and uses the drug. The FDA defines it clearly: two drugs are bioequivalent if they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate. That means the peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure over time (AUC) must match closely between the generic and the brand-name drug.

This isn’t just theory. It’s the law. Under the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act, generic manufacturers don’t have to repeat expensive clinical trials proving a drug works. Instead, they prove it behaves the same way in the body. If the numbers match within strict limits, the FDA says the drugs are therapeutically equivalent. That’s why millions of Americans safely switch to generics every day.

The 80-125% Rule: The Gold Standard

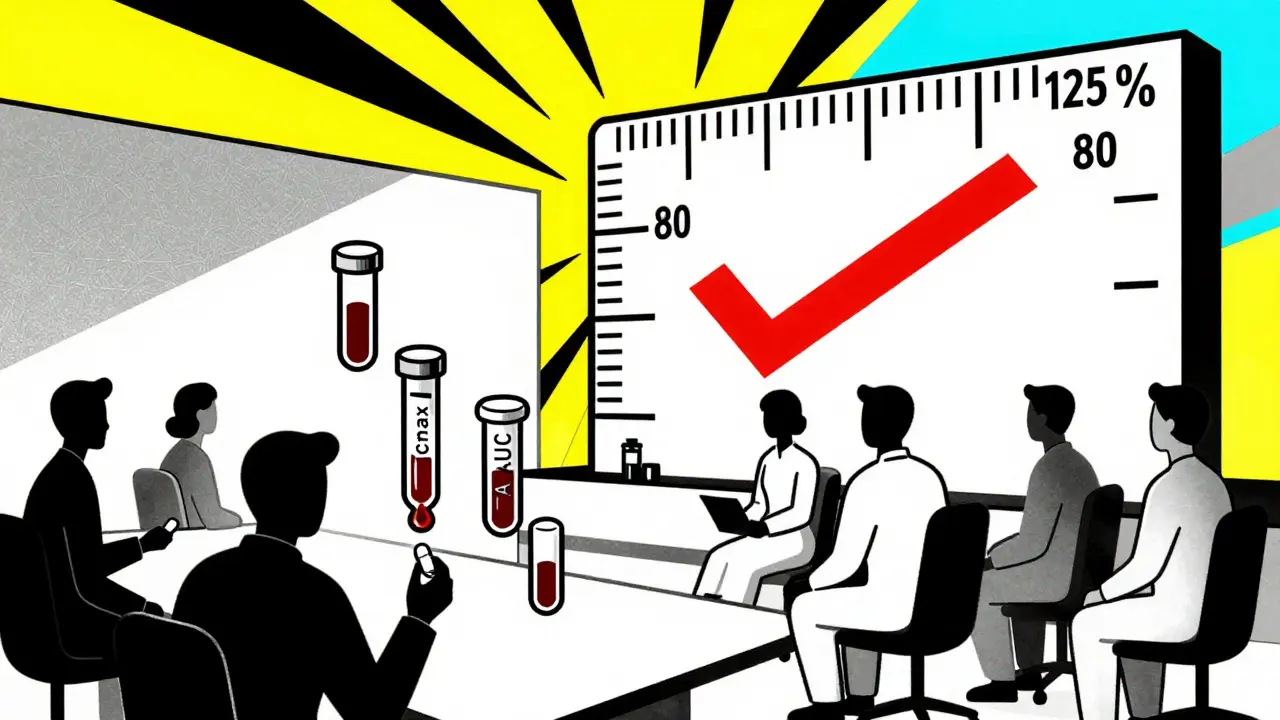

The FDA’s main tool for measuring bioequivalence is the 80-125% rule. Here’s how it works: in a clinical study, healthy volunteers take both the generic and the brand-name drug, usually under fasting conditions. Blood samples are taken over time to track how much of the drug enters the bloodstream.

The data is analyzed using the geometric mean of Cmax and AUC. The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic to the brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. That’s it. If the interval stays inside those bounds, the drugs are considered bioequivalent.

This rule has been in place since 1992 and has never changed for standard drugs. It’s not arbitrary-it’s based on decades of pharmacokinetic data and statistical modeling. Even if the generic delivers 82% of the brand’s concentration, it’s still approved. Why? Because the body can handle that small variation without affecting safety or effectiveness.

When the Rules Get Tighter

Not all drugs are created equal. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where even a tiny change in blood level can cause harm or toxicity-the FDA demands stricter standards. Drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, and phenytoin fall into this category.

For these, the acceptable range shrinks to 90-111%. That’s a much tighter window. The reason? A 10% drop in levothyroxine might leave a patient hypothyroid. A 10% spike could trigger heart rhythm problems. The FDA doesn’t take chances here. Manufacturers must prove their generic matches the brand with far greater precision.

For highly variable drugs-where the body absorbs the drug differently from person to person-the FDA allows something called scaled average bioequivalence (SABE). This method adjusts the acceptance range based on how much the drug varies in the population. It’s a smarter, more flexible approach for tricky drugs like certain anticonvulsants or blood thinners.

When You Don’t Need a Human Study

Not every generic drug needs a full clinical trial. The FDA allows biowaivers for certain products where absorption isn’t a concern. For example:

- Oral solutions with the exact same ingredients as an approved brand

- Topical creams or lotions meant to work on the skin, not in the bloodstream

- Ophthalmic and otic solutions

- Inhalant anesthetics

For these, manufacturers can use in vitro tests instead. They prove the drug releases at the same rate in lab conditions, matches the pH, and has the same particle size and solubility as the brand. This is called the Q1-Q2-Q3 framework: identical active ingredients (Q1), same dosage form and concentration (Q2), and equivalent physical properties (Q3).

Biowaivers save manufacturers months-and millions of dollars. They also speed up access to affordable medicines. The FDA has approved over 1,200 biowaiver pathways for specific products as of 2023.

What Happens in the Study

A typical bioequivalence study involves 24 to 36 healthy adults. They’re randomly assigned to take either the generic or the brand-name drug first, then switch after a washout period. This crossover design reduces individual differences from affecting results.

Studies are done under fasting conditions to get a clear picture of absorption. But if the drug is meant to be taken with food, a second study is required under fed conditions. Why? Some drugs, like certain antibiotics or cholesterol meds, absorb much better with food. The generic must match the brand in both scenarios.

All studies must follow Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) rules. Blood samples are handled carefully, stored properly, and analyzed with validated methods. The FDA checks every detail-from how the drug was manufactured to how the lab measured concentrations.

Why So Many Applications Get Rejected

Despite clear guidelines, nearly 60% of generic drug applications get rejected on the first try. Why? Common mistakes include:

- Using the wrong number of volunteers

- Poor sampling times (missing the peak concentration)

- Inaccurate lab methods

- Not following the product-specific guidance (PSG)

Companies that stick to the FDA’s product-specific guidances-there are over 2,100 of them-have a 68% first-time approval rate. Those who don’t? Only 29%. The PSGs are detailed documents for each drug. They tell you exactly how to design your study, what endpoints to measure, and what statistical methods to use. Skipping them is like building a house without blueprints.

The cost of failure is high. A single bioequivalence study can run $500,000 to $2 million. One misstep can delay approval by a year or more.

The Future: New Tools for Tougher Drugs

The FDA is updating its approach for complex generics-like inhalers, topical creams, and injectables. Traditional bioequivalence methods don’t always work for these. So the agency is turning to new science:

- Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling: computer simulations that predict how a drug behaves in the body based on its chemistry and human biology

- In vitro permeation testing (IVPT): measuring how well a topical drug moves through skin layers

- Advanced in vitro release testing (IVRT): simulating how a drug releases from a tablet or cream in lab conditions

These tools are already being used for some products. By 2024, the FDA plans to release draft guidance for 45 complex drug types. This means more generics will reach the market faster-without cutting corners on safety.

Why It Matters to You

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they cost only 23% of what brand-name drugs do. That’s billions saved every year. Bioequivalence studies are the reason this system works. They ensure you’re not getting a cheaper version that might not work-or worse, cause harm.

The FDA doesn’t approve generics because they’re cheaper. They approve them because they’re proven to be the same. That’s the promise of bioequivalence. And it’s why you can trust your prescription, no matter which label is on the bottle.

Do generic drugs have the same active ingredients as brand-name drugs?

Yes. By law, generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. The FDA requires this for pharmaceutical equivalence before even considering bioequivalence.

Can a generic drug be less effective than the brand?

No-not if it’s FDA-approved. Bioequivalence studies prove the generic delivers the same amount of drug into your bloodstream at the same rate. If it didn’t, the FDA would not approve it. Thousands of studies and decades of real-world use confirm this.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

Sometimes, differences in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) can cause minor side effects, like stomach upset or allergic reactions. But these don’t affect how well the drug works. If a patient feels different on a generic, it’s usually due to placebo effect, changing brands frequently, or an unrelated health change-not lack of bioequivalence.

How long does a bioequivalence study take to complete?

A single study typically takes 3 to 6 months from start to finish. This includes recruiting volunteers, dosing, blood sampling, lab analysis, and data review. But the entire ANDA process-including manufacturing, documentation, and FDA review-can take 14 to 18 months.

Are bioequivalence studies required for all generic drugs?

No. Some products qualify for biowaivers based on their formulation and route of administration. For example, eye drops, certain inhalers, and topical creams may not need human studies if they meet specific in vitro criteria. But for most oral pills and injections, bioequivalence studies are mandatory.

Scottie Baker January 14, 2026

Bro, I took a generic for my blood pressure and felt like a zombie for a week. Turns out it was the filler, not the drug. FDA doesn't care if you feel like crap as long as the numbers match. 🤷♂️

Kimberly Mitchell January 15, 2026

So let me get this straight - you’re telling me a pill that costs $5 is chemically identical to one that costs $50, but I’m supposed to trust it because some math says so? Sounds like corporate propaganda.

Robin Williams January 15, 2026

GENERIC DRUGS ARE THE PEOPLE’S MEDICINE. 💪 The FDA didn’t invent bioequivalence to screw over pharma - they did it so grandma can afford her pills. Stop whining and take the damn tablet.

Gregory Parschauer January 15, 2026

Let’s be real - the 80-125% rule is a joke. It’s not science, it’s a political compromise. If you’re talking about warfarin or levothyroxine, that’s not bioequivalence - that’s Russian roulette with your endocrine system. And don’t even get me started on the biowaivers for topical creams. You can’t measure skin permeation with a beaker and a wish.

The FDA’s entire framework was designed for 1992 pharmacokinetics. We’ve got AI-driven PBPK models now, and they’re still using geometric means and confidence intervals like it’s 1997. The system is ossified. It’s not broken - it’s fossilized.

And yet, somehow, it works. Millions of people take generics without incident. So why do I feel like we’re all just gambling on a statistical loophole? Because the truth is, we don’t know what ‘same’ means anymore. We just know we can’t afford not to pretend.

Meanwhile, the manufacturers? They’re gaming the PSGs like chess masters. One typo in the sampling schedule and you’re back to square one. $2 million down the drain because someone forgot to calibrate the HPLC after lunch.

And don’t even mention the placebo effect. Patients swear generics ‘don’t work’ - but it’s not the drug. It’s the brand loyalty. The color of the pill. The shape. The damn logo on the bottle. We’ve conditioned people to equate price with potency. And the FDA? They’re just trying to keep the lights on while the whole system’s held together by duct tape and regulatory inertia.

Randall Little January 17, 2026

So… if a drug’s absorption varies wildly between people, the FDA lets the acceptance range expand? That’s not flexibility - that’s surrender. You’re not adjusting for variability, you’re just lowering the bar until the generic passes. Brilliant.

Anny Kaettano January 17, 2026

Actually, SABE isn’t lowering the bar - it’s recognizing biological reality. Some drugs are just inherently variable. Forcing a rigid 80-125% on a drug like clopidogrel would mean denying access to generics for years. SABE lets us approve safe, effective drugs faster without compromising safety. It’s science adapting to complexity, not giving up.

And yes - the FDA’s guidelines are meticulous. The 2,100+ PSGs? They’re not suggestions. They’re the blueprint. If you skip them, you’re not a rebel - you’re just incompetent. And yes, it’s expensive. But so is a hospital stay because someone’s INR went off the rails from a bad generic.

James Castner January 19, 2026

It is profoundly humbling to contemplate the magnitude of public health infrastructure that undergirds the seemingly mundane act of purchasing a $3 generic tablet. The convergence of pharmacokinetic science, statistical rigor, regulatory foresight, and industrial compliance - all orchestrated to ensure that a person in rural Mississippi receives the same therapeutic benefit as a person in Manhattan - this is not merely policy. This is civilization functioning as it ought to.

And yet, we are a culture that reduces complex systems to memes and mistrust. We equate cost with quality, brand with virtue, and ignorance with skepticism. The FDA does not approve generics because they are cheap. They approve them because they are proven - rigorously, repeatedly, and with statistical confidence exceeding 90%.

The biowaivers? Not loopholes. They are elegant applications of physicochemical principles. When a drug is administered as an oral solution with identical excipients, and its dissolution profile matches the innovator product across pH gradients - why subject a healthy volunteer to venipuncture? The science is settled. The ethics are clear.

Let us not forget: 90% of prescriptions filled in this country are generics. That is not a failure of regulation - it is its greatest triumph. Billions saved. Lives extended. Access democratized. And still, we whisper doubts in the pharmacy aisle, as if the system were a house of cards - when in truth, it is a cathedral built by thousands of scientists, regulators, and technicians who never asked for applause.

So next time you pick up a generic - pause. Thank the system. And swallow it without fear.

Angel Tiestos lopez January 20, 2026

bro the FDA just wants you to live and not go broke 💸💊 but also… why do generics always make me feel like i’m on a low-budget antidepressant? 🤔 maybe it’s the dye… or my brain playing tricks 🤷♂️

John Tran January 21, 2026

Okay so I read this whole thing and I’m still confused - like, if the drug’s the same, why do I feel different on the generic? Is it placebo? Is it the filler? Is it the fact that the pill looks like a tiny blue rock instead of a fancy white oval with a logo? I mean, I’ve been on the same med for 8 years and when they switched me to generic, I started having weird dreams about falling off cliffs. Coincidence? I think not. The FDA doesn’t test for dream quality. That’s the flaw. That’s the crack in the system. They measure blood levels, sure, but what about the soul? What about the subconscious? You can’t quantify existential dread with an AUC. And yet… we’re all just supposed to trust the math? I don’t trust math. Math doesn’t care if you cry at 3 a.m. because your pill changed color.

Also, I think the FDA is run by robots. Or maybe just very tired accountants. Someone needs to tell them that humans aren’t lab rats. We’re emotional, irrational, dream-having creatures who need to believe in the shape of our pills. That’s not weakness - that’s humanity. And if your system can’t account for that… then it’s not bioequivalence. It’s just bureaucracy pretending to be science.

Acacia Hendrix January 22, 2026

The entire bioequivalence paradigm is a neoliberal fiction designed to extract profit under the guise of accessibility. The 80-125% range isn’t evidence-based - it’s a product of industry lobbying. The FDA’s ‘rigorous’ standards are performative compliance rituals. Real therapeutic equivalence would require pharmacodynamic endpoints, not just pharmacokinetic curves. But that would be expensive. And inconvenient. So we settle for statistical mirages and call it progress.

Meanwhile, patients are conditioned to believe that cost equals moral virtue. The real tragedy? We’ve been sold the lie that cheaper is better - when what we really need is transparency. Why not label generics with their actual Cmax/AUC ratios? Let the consumer decide. But no - we’d rather have a regulatory charade than a market of informed choices.

And let’s not forget: the same corporations that profit from brand-name drugs often own the generic versions too. This isn’t competition. It’s consolidation dressed in beige pills.

Adam Vella January 24, 2026

It is axiomatic that the FDA’s bioequivalence framework represents one of the most sophisticated and empirically grounded regulatory paradigms in modern pharmacology. The 80-125% confidence interval is not arbitrary, but rather derived from the log-normal distribution of pharmacokinetic parameters, validated across decades of clinical data. The application of geometric means and the use of ANOVA-based statistical models are not concessions - they are the product of rigorous mathematical and biological reasoning.

Furthermore, the differentiation between standard and narrow therapeutic index drugs reflects a nuanced understanding of clinical risk stratification. The adoption of SABE for highly variable drugs demonstrates adaptive regulatory science - not regulatory failure. The biowaiver protocols, grounded in the Q1-Q2-Q3 framework, are elegant applications of dissolution kinetics and physicochemical equivalence.

It is lamentable that public discourse reduces this intricate, evidence-based system to mere suspicion and anecdote. The fact that 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics - and that adverse event rates remain statistically indistinguishable from brand-name counterparts - is not a coincidence. It is the result of a system that prioritizes public health over profit.

To question bioequivalence is to question the foundations of modern therapeutic science. The data is clear. The methodology is sound. The outcomes are proven. The skepticism is not intellectual - it is emotional.

Angel Molano January 25, 2026

Stop complaining. The science works. Take the pill.